Although the Spanish-American War lasted for only a few months in 1898, the legacy of this brief yet transformative conflict is marked on the landscape of Arlington National Cemetery. Arlington has more Spanish-American War memorials than any other single site in the United States, including the USS Maine Memorial, the Spanish-American War Memorial, the Spanish-American War Nurses Memorial and the Rough Riders Memorial. In addition, hundreds of U.S. service members and nurses who died in the war with Spain are buried at Arlington—many in Sections 21, 22 and 24, near the related memorials.

Our new Education Program features a module on the Spanish-American War, in part due to its significance within the context of Arlington National Cemetery’s own history. The Spanish-American War was the United States’ first major international conflict after Arlington’s establishment as a national cemetery in 1864, during the Civil War. Between 1864 and 1898, Arlington had risen in prominence to become the nation’s premier military cemetery, partly as a result of the popular Decoration Day ceremony held at the cemetery every May since 1868. During the Spanish-American War, the U.S. government also adopted a new policy to repatriate (return to the United States) the remains of all service members who died overseas. Arlington National Cemetery consequently expanded, and on May 21, 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt dedicated the Spanish-American War Memorial in Section 22—the first of several memorials at Arlington that commemorate the war.

Dedication of the USS Maine Memorial, February 15, 1915. (Library of Congress)

As our Education module explains, the Spanish-American War indelibly shaped not only the cemetery itself, but also the broader history of the United States and the world. The U.S. ambassador to Britain, John Hay, famously described it as a “splendid little war.” The United States declared war against Spain on April 25, 1898, three months after the USS Maine exploded in the harbor of Havana, Cuba, then a Spanish colony. At the time, Americans widely blamed Spain for the disaster, which was later determined to have likely been an accident. An armistice concluded hostilities on August 12, 1898, with a formal peace treaty signed on December 10, 1898.

Yet this brief war can hardly be considered “little” in its consequences. The Spanish-American War inaugurated the United States as a bona fide global power, on par with the empires of Europe. Having recently expanded west across the American continent, the nation now gained its first overseas territories: the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines, ceded to the U.S. in the peace treaty. Cuba became nominally independent, but the U.S. government quickly asserted economic and political control over the island, solidifying its dominance in the Western Hemisphere. And, in vanquishing the formidable Spanish fleet, the United States flexed its new naval strength. In sum, the Spanish-American War paved the way for the 20th century to be an “American century” (to use the catchphrase later coined by publisher Henry Luce).

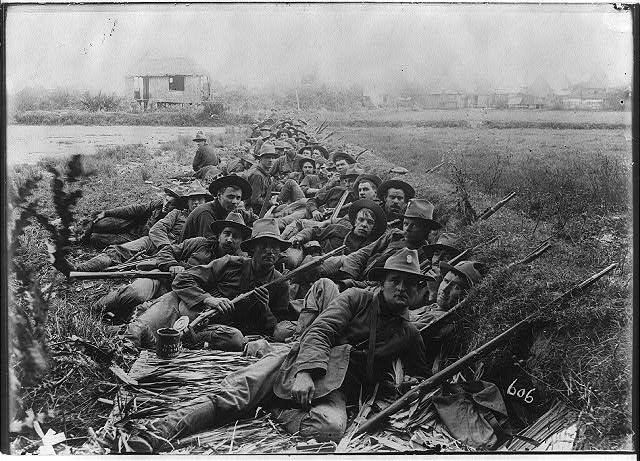

The 20th Kansas Volunteer Infantry in trenches in the Philippines, ca. 1899. (Library of Congress)

However, the Spanish-American War also led the United States to become embroiled in brutal anti-insurgency warfare against nationalists in the Philippines, which lasted from 1899 to 1902. The Philippine-American War directly resulted from the Spanish-American War, and the two conflicts can be understood together. While an overwhelming majority of Americans supported war against Spain, U.S. intervention in the Philippines sharply divided the American public. This messy, protracted conflict raised difficult questions about imperialism, democracy, military tactics, and the relation between race and U.S. citizenship. Was the United States, with its newly acquired overseas territories, now an empire? If so, how could the nation’s imperial power be reconciled with its claims to stand for democracy? Did the objectives of the war in the Philippines justify military tactics that many Americans considered extreme? Should non-white people in overseas U.S. territories be treated as full American citizens—especially in the context of racial segregation and intensifying anti-immigrant sentiment at home? Debates over these issues—which lie at the core of American identity—continue today, and can be seen as part of the Spanish-American War’s longer legacy.

► Explore these questions in depth in units on “Historical Opinions of the Spanish-American War” and “What Is the United States of America?”

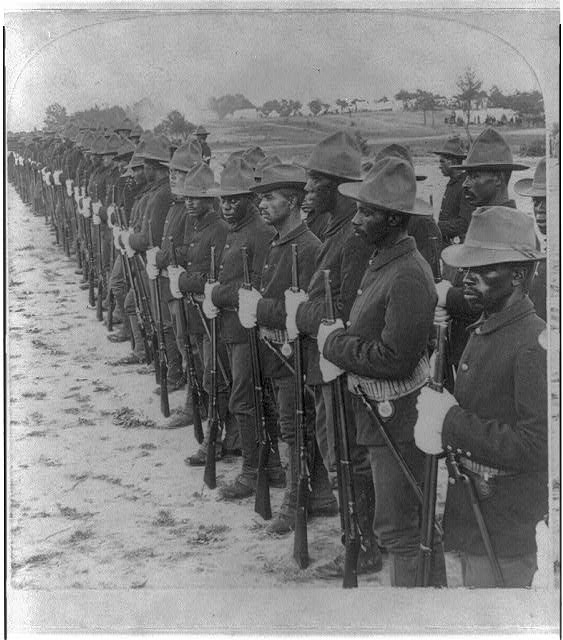

Buffalo Soldiers, ca. 1899. (Library of Congress)

The Spanish-American War also reflected the increasing diversity of the U.S. military at the turn of the 20th century. Although the military remained segregated by race, African Americans served honorably in several all-Black U.S. Army units: the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments and the 24th and 25th Regiments. Established in 1866, these units had previously served on the United States’ western frontier, where they came to be known as the “Buffalo Soldiers.” (According to many accounts, this nickname was given to them by the Native Americans they encountered and fought in the West.) During the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars, Buffalo Soldier units served both in Cuba and in the Philippines. In Cuba, the 10th Cavalry participated in the famous Battle of San Juan Hill, alongside Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders; five members earned the Medal of Honor for their heroism.

► Read African American soldiers’ firsthand accounts of their experiences, and learn more about the Buffalo Soldiers in our African American Experience at Arlington National Cemetery education module.

Women, too, served in the Spanish-American War as nurses. Indeed, the war marked a turning point in the United States’ recognition of female nurses’ contributions to military efforts. For the first time, professionally trained women could serve with the U.S. armed forces as contract nurses, and more than 1,500 women served. Stationed in Cuba and the Philippines, they not only treated combat injuries, but also battled the debilitating tropical diseases (yellow fever, malaria, dengue fever) that afflicted U.S. service members and jeopardized the war effort.

► Learn about these remarkable nurses, and how the war expanded roles for women in the U.S. military, in our “Nurses in the Spanish-American War” unit.

U.S. Army contract nurses, 1898. (National Library of Medicine)

Explore the entire education module to learn more about the Spanish-American War and its fascinating, complex legacies. In the process, you’ll also immerse yourself in the rich, diverse history of Arlington National Cemetery. Materials include:

• Walking tours of Spanish-American War monuments and gravesites: Use these self-guided tours during your visit, or to explore the cemetery virtually from home.

• Personal accounts of the war, from a Rough Rider, an officer and an enlisted sailor on Admiral George Dewey’s USS Olympia, “Buffalo Soldiers” and more

• Primary source readings: Alfred Thayer Mahan on naval power, Carl Schurz on “manifest destiny,” William Jennings Bryan’s critique of imperialism, and more

• Political cartoons and photographs

• Timelines, maps and related activities

Who can use these materials?

Anyone can use these free materials! We have developed resources tailored to the following audiences:

• Elementary School

• Middle School

• High School

• Lifelong Learners (anyone beyond school age with the curiosity to learn)

Do I have to use these materials onsite at Arlington National Cemetery? Or can I use them at home?

The materials are designed to be used from anywhere in the world! While the cemetery remains closed to visitors, and as many students begin the school year in a virtual learning environment, we encourage you to use our Education Program materials wherever you reside. When the cemetery does open to the public in the future, the materials can also be used before, during and after a visit.

► Click here for more information about Arlington National Cemetery’s Education Program, including two other modules: The African American Experience at Arlington National Cemetery and Understanding Arlington.