By Anna Gibson Holloway, PhD

Special Programs Team Leader, Histories Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command

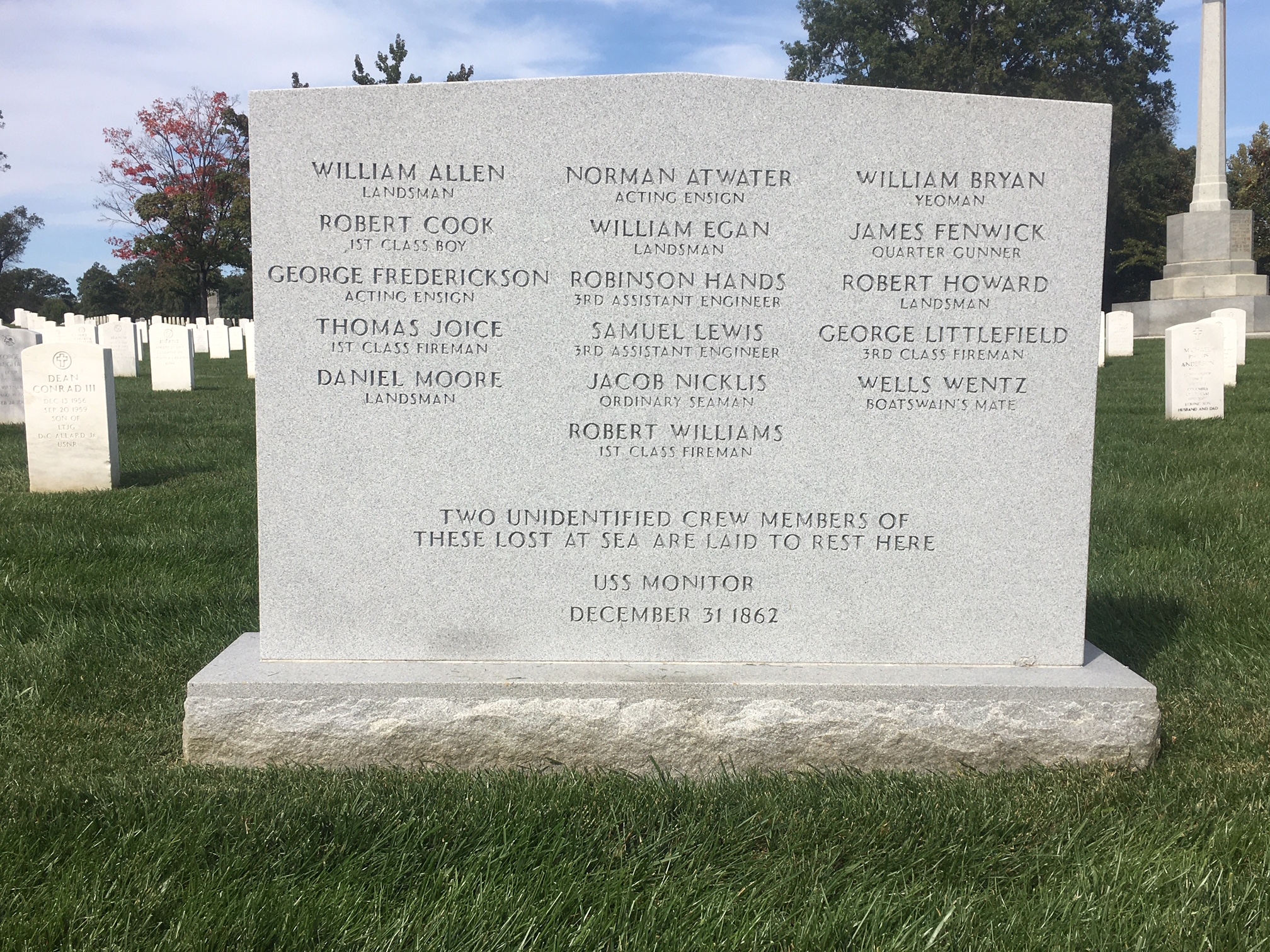

In Section 46 of Arlington National Cemetery, there stands a simple monument engraved with sixteen names. Nestled near the Challenger, Columbia and Iran Rescue Mission monuments, this stone rests in the shadow of USS Maine’s mast, which dominates the landscape near Memorial Amphitheater. Beneath this unassuming stone marker is the final resting place of two unknown sailors from the Union ironclad ship, Monitor. Their journey from the Monitor wreck site off of North Carolina to Arlington spanned a century and a half, and they traveled halfway around the globe before finally being laid to rest here. Their story is as remarkable as the story of the ship in which they served.

In Section 46 of Arlington National Cemetery, there stands a simple monument engraved with sixteen names. Nestled near the Challenger, Columbia and Iran Rescue Mission monuments, this stone rests in the shadow of USS Maine’s mast, which dominates the landscape near Memorial Amphitheater. Beneath this unassuming stone marker is the final resting place of two unknown sailors from the Union ironclad ship, Monitor. Their journey from the Monitor wreck site off of North Carolina to Arlington spanned a century and a half, and they traveled halfway around the globe before finally being laid to rest here. Their story is as remarkable as the story of the ship in which they served.

USS Monitor was the brainchild of Swedish-American inventor John Ericsson. The U.S. Navy built Monitor in response to the Confederate threat of an ironclad vessel rising on the ways at Gosport Navy Yard in Portsmouth, Virginia in 1861. The Confederate ironclad ship, built upon the bones of the scuttled steam-screw frigate Merrimack, would ultimately bear the name CSS Virginia and would meet Monitor in a watery battlefield off of Hampton Roads, Virginia on March 9, 1862 in the first-ever battle between ironclad warships. Although the battle ended in a draw, it indicated that the future of naval warfare would be one of iron and steam and engineers. Neither vessel survived beyond 1862, however; the Virginia was scuttled by its own crew on May 11, 1862 as U.S. Army troops descended on Norfolk, Virginia. The explosion was felt for miles around. Monitor remained in Virginia, serving on the James River in support of General George McClellan’s failed Peninsular Campaign, until it was sent north to the Washington Navy Yard for much-needed repairs in the fall of 1862. There, the little ironclad was the talk of the town, and the streets around the Yard were jammed with carriages carrying men and women clamoring to see the vessel.

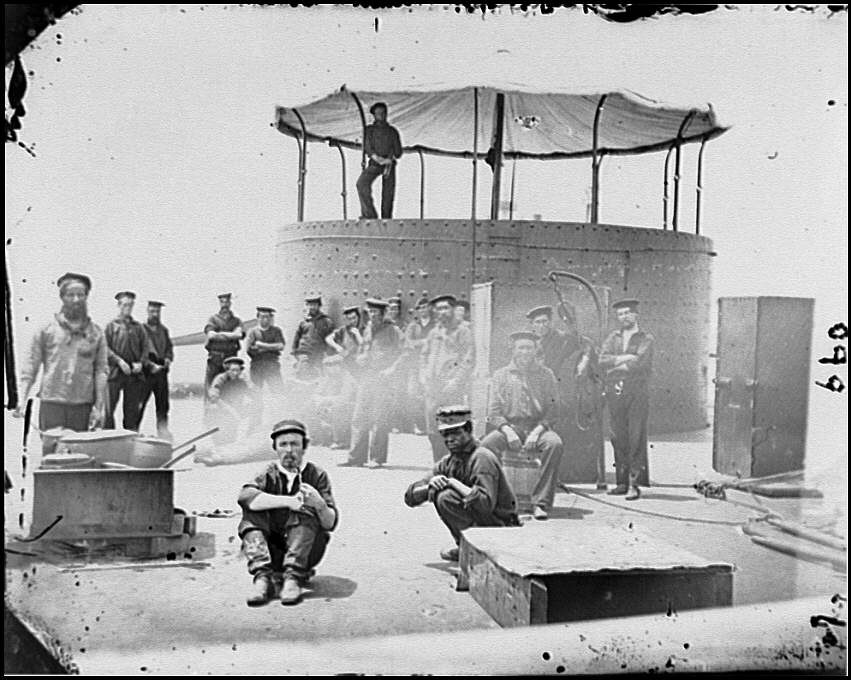

Sailors on deck of U.S.S. Monitor; cookstove at left. James River, Va. July 9, 1862. James F. Gibson, photographer. (Library of Congress)

On Christmas Eve 1862, Monitor was once again in Hampton Roads when it received orders to proceed to Beaufort, North Carolina to await further instruction. Its commanding officer, John Pine Bankhead, was exhorted to “Avail yourself of the first favorable weather for making the passage.” The immediate weather was less than favorable, so on Christmas Day, some of the “Monitor Boys” (as the crew proudly referred to themselves) were allowed ashore where they mixed, at first jovially and later angrily, with British sailors, also on shore leave. They were “on the best of terms till the parties got too much whiskey,” recalled Paymaster William Keeler. Upon their return to Monitor, “there seemed to be a sort of general mass, black eyes, bloody noses, & battered faces.”

On December 29, 1862, Monitor finally left Hampton Roads in tow of the sidewheel steamer Rhode Island. While the passage was initially calm, conditions deteriorated dramatically as they proceeded south. Just past midnight on December 31, 1862, approximately 16 miles off the coast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, the little ironclad succumbed to the waves and sank – taking four officers and twelve crew members to the bottom of the Atlantic. Survivors watched in horror from the deck of the Rhode Island. Paymaster William Keeler wrote forlornly, “The Monitor is no more…What the fire of the enemy failed to do, the elements have accomplished.”

There Monitor lay, undisturbed for over a century until discovered in 1973 by a team of researchers from the Duke University Marine Lab in Beaufort, North Carolina. The discovery was announced in March 1974, and the wreck site became the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) first National Marine Sanctuary in 1975. Artifact recoveries began in the 1970s, but accelerated in the early 2000s when NOAA teams noticed the rapid deterioration of the vessel. In all, NOAA, the U.S. Navy, and The Mariners’ Museum (Newport News, VA) recovered approximately 210 tons of the ironclad, culminating in the 2002 turret recovery.

Throughout the recovery missions, team members had been keenly aware that Monitor remained a war grave. They further understood that the turret itself might be a tomb, given that it was the only means of egress on the night of the sinking. Navy divers from the Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit 2 (MDSU2) out of Little Creek, Virginia were the first to discover shipmates—as they referred to the Monitor crew—separated from them in time nearly 140 years while they excavated a portion of the turret on the ocean bottom. Finally, on August 5, 2002, the turret rose from the depths, and a crane operator gingerly placed it onto the deck of the salvage barge Wotan.

Excavations continued at The Mariners’ Museum. Ultimately, archaeologists recovered two sets of human remains from the turret. Artifacts found nearby hinted at possible identities—initials on silverware, boots, shoes and more. But the two remained unknown. They then embarked on a further journey to the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii (now the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, or DPAA). There, scientists performed forensic analysis to try to determine their identities.

One set of remains, designated CIL 2002-097-I-01, was determined to be a young Caucasian man between the ages of seventeen and twenty-four. He was approximately 5’7” tall and had a broken, but healing, nose. The other individual, designated CIL 2002-097-I-02, was older—between thirty and forty years of age. His was a bit shorter, standing at approximately 5’6”. He likely had a slight limp, and was a heavy smoker, judging from the pipe groove in his teeth. He, too, had a broken, but healing, nose. It is possible these two men were among those whose shore leave on Christmas Day turned belligerent in their mix-up with the British sailors in Hampton Roads. No artifacts associated directly with the two bodies indicated that they were officers. Here were likely two of the Monitor Boys.

But which two Monitor Boys? Race, height and age helped narrow down some of the possibilities—though none of the sixteen were completely discounted. In an attempt to raise public awareness about the two, NOAA worked with the Forensic Anthropology and Computer Enhancement Services (FACES) lab at Louisiana State University to create facial reconstructions in the hope that they might be recognized from old photographs or through family resemblance. NOAA and the U.S. Navy sought out living descendants of the sixteen men who went down with the Monitor; many provided DNA samples. No positive matches were made, however. The facial reconstructions, while giving a semblance of life to the two long-dead sailors, did not definitively match any known photographs of the lost, although the older of the two somewhat resembled Robert Williams, a first class fireman from Wales.

But which two Monitor Boys? Race, height and age helped narrow down some of the possibilities—though none of the sixteen were completely discounted. In an attempt to raise public awareness about the two, NOAA worked with the Forensic Anthropology and Computer Enhancement Services (FACES) lab at Louisiana State University to create facial reconstructions in the hope that they might be recognized from old photographs or through family resemblance. NOAA and the U.S. Navy sought out living descendants of the sixteen men who went down with the Monitor; many provided DNA samples. No positive matches were made, however. The facial reconstructions, while giving a semblance of life to the two long-dead sailors, did not definitively match any known photographs of the lost, although the older of the two somewhat resembled Robert Williams, a first class fireman from Wales.

Pictured, above right: Clay model recreations of the faces of two USS Monitor sailors whose remains were found in the USS Monitor gun turret in 2002. Images on the right are computer enhanced versions showing what the unknown sailors may have looked like while aboard the USS Monitor in 1862. (Forensic constructions: Louisiana State University)

All of those working on the multi-agency Monitor team agreed that these men should be interred at Arlington National Cemetery. With no next of kin available, the U.S. Navy stepped into that role, and DPAA released the remains to the Navy in early 2013. Since they were unknown, the Navy chose to list the names of all sixteen men on the gravesite marker, thus ensuring that the names of the two would be included. With a military and NOAA escort, the two Monitor sailors traveled from Hawaii to Arlington to be honored.

On March 8, 2013, relatives of Monitor officers and crew—as well as the ad hoc family that had been created by NOAA, Navy divers, archaeologists, historians, curators and conservators—gathered at the Fort Myer Memorial Chapel for a private funeral service. There, Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus reminded the group that “[w]hile Naval tradition holds the site of a shipwreck as hallowed ground and a proper final resting place for sailors who perish at sea, this ceremony pays tribute not only to the two sailors being interred, but to all who died when Monitor sank so many years ago during the Civil War. Little is certain in military service, but we can guarantee the Navy will always remain committed to honoring those who pay the ultimate price defending our nation.”

Members of the U.S. Navy Ceremonial Guard escort the remains of two sailors recovered from the ironclad USS Monitor during a military funeral at Arlington National Cemetery. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Todd Frantom/Released)

And so the two Monitor Boys began their final journey. The flag-draped caskets were placed on horse-drawn caissons for the brief trip to their final resting place. The funeral attendees followed as the caissons wound their way through the cemetery. At Memorial Amphitheater, hundreds of members of the general public had gathered to take part in this final, solemn moment. Under a ragged sky, the exacting precision that is a military funeral unfolded and the sound of three gun volleys and “Taps” reverberated in the cool air. Though only two men were laid in the grave, their presence honored all sixteen.

Sixteen names are on the face of the memorial: sixteen men who volunteered to serve in an experimental vessel at a time when the very fabric of our nation was in peril. They were part of a crew that was as multicultural as the nation. Over the course of Monitor’s brief career, 108 men and boys served in it—the youngest was 18, the oldest 43. The men hailed from New York, Rhode Island, Maine and Virginia, among other states. Seventeen crew members came from Ireland, four each from England and Sweden, two each from Germany and Wales, and others from Austria, Scotland, Canada and Norway. Eight were African-American—some had escaped from slavery, while others were already free. All of them were heroes, and this monument at Arlington National Cemetery highlights the sacrifice that sixteen U.S. Navy sailors made in the defense of our nation.

Names Engraved on the Monument

|

William Allen

|

Landsman

|

England

|

|

Norman Atwater

|

Acting Ensign

|

Connecticut

|

|

William Bryan

|

Yeoman

|

New York

|

|

Robert Cook

|

1st Class Boy

|

Virginia

|

|

William Egan

|

Landsman

|

Ireland

|

|

James Fenwick

|

Quarter Gunner

|

Scotland

|

|

George Frederickson

|

Acting Ensign

|

Norway

|

|

Robinson Hands

|

3rd. Assistant Engineer

|

Maryland

|

|

Robert Howard

|

Landsman

|

Virginia

|

|

Thomas Joice

|

1st Class Fireman

|

Ireland

|

|

Samuel Lewis

|

3rd Assistant Engineer

|

Maryland

|

|

George Littlefield

|

3rd Class Fireman

|

Maine

|

|

Daniel Moore

|

Landsman

|

Virginia

|

|

Jacob Nicklis

|

Ordinary Seaman

|

New York

|

|

Wells Wentz (aka John Stocking)

|

Boatswain’s Mate

|

New York

|

|

Robert Williams

|

1st Class Fireman

|

Wales

|

See also: