To commemorate the 2021 centennial of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, as well as the U.S. Navy’s 246th birthday on October 13, we honor USS Olympia—the legendary Navy ship that brought the World War I Unknown Soldier home to the United States from France in 1921.

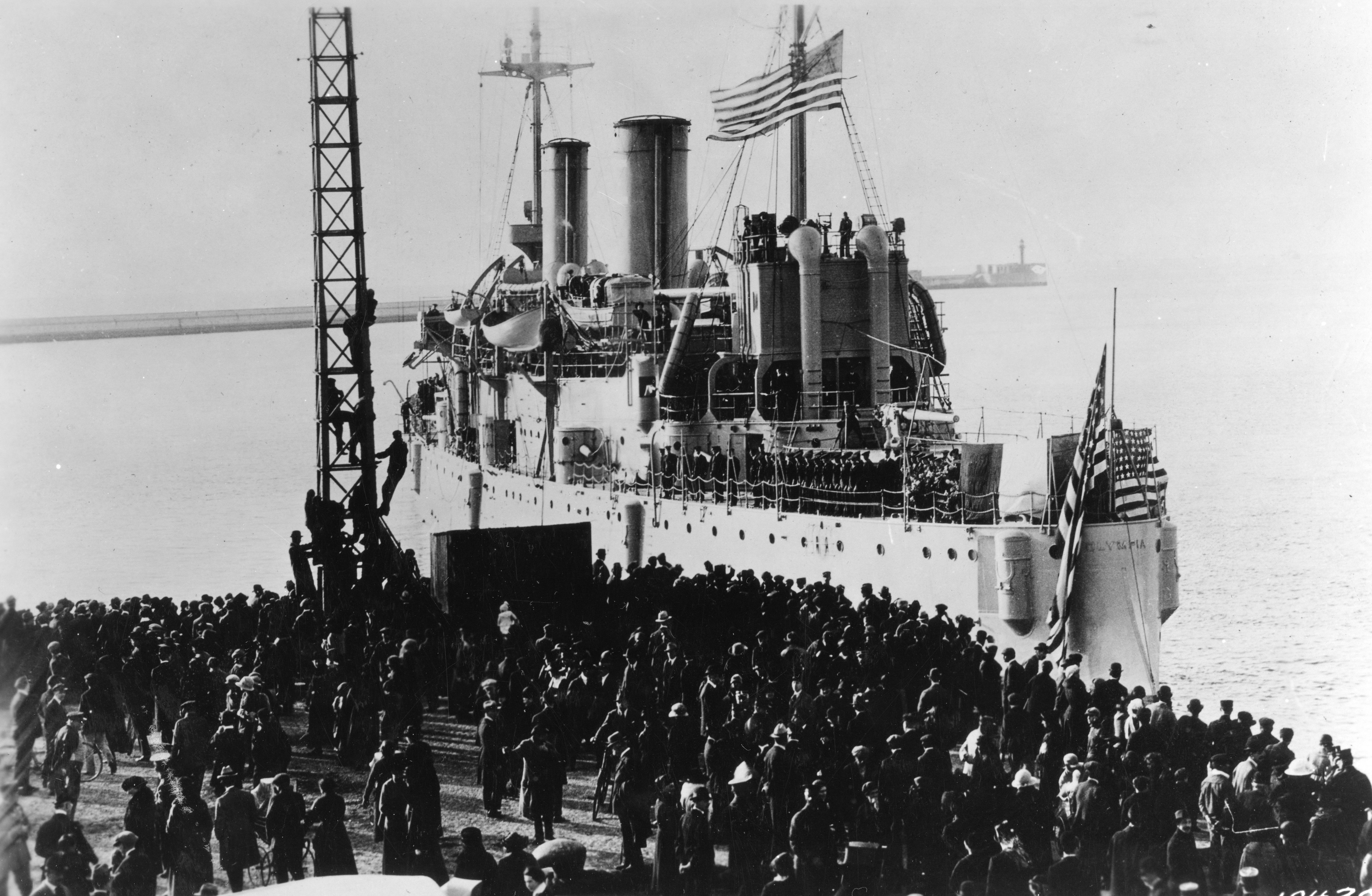

USS Olympia leaving Le Havre, France, October 25, 1921. (National Archives)

USS Olympia (C-6) is the oldest steel-hulled American warship afloat and one of the most recognizable names in the annals of U.S. Navy history. Olympia was commissioned on November 5, 1892 and assigned to the Asiatic Squadron in 1895. During the Spanish-American War, Olympia defeated the Spanish fleet in the Battle of Manila Bay on May 1, 1898. The distinguished ship’s last major mission transported the Unknown Soldier from France to the United States for burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

Prior to transporting the Unknown, Olympia was best known for its service in the Spanish-American War. On January 3, 1898, Commodore George Dewey assumed command of Olympia as his flagship. Shortly thereafter, on February 15, 1898, the battleship USS Maine exploded in the harbor of Havana, Cuba, a Spanish colony. Outraged Americans suspected that Spain had planted a mine in the harbor. “Remember the Maine!” became a popular rallying cry among Americans who supported going to war against Spain. (The Mast of the Maine has been preserved as a memorial at Arlington National Cemetery. Located near Memorial Amphitheater and the Tomb, it stands alongside the remains of U.S. service members, including unknowns, who died in the explosion.)

On February 25, 1898, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt ordered Dewey to keep his squadron full of coal in the event of war with Spain. Dewey’s duty, noted Roosevelt, would be to prevent the Spanish squadron from leaving the Asiatic coast and to engage in offensive operations in the Philippine Islands (also colonized by Spain).

After Congress declared war against Spain on April 25, 1898, Secretary of the Navy John Davis Long ordered Dewey to proceed immediately to the Philippines (another Spanish colony) and to use “utmost endeavors” to capture or destroy the Spanish fleet. Olympia engaged Spanish ships and shore batteries with great success. The resulting victory over Spanish naval forces at Manila Bay strengthened American sea power in Asia and propelled Olympia to worldwide fame. As the United States expanded its empire abroad at the turn of the twentieth century, the ship became a source and symbol of national power.

After Congress declared war against Spain on April 25, 1898, Secretary of the Navy John Davis Long ordered Dewey to proceed immediately to the Philippines (another Spanish colony) and to use “utmost endeavors” to capture or destroy the Spanish fleet. Olympia engaged Spanish ships and shore batteries with great success. The resulting victory over Spanish naval forces at Manila Bay strengthened American sea power in Asia and propelled Olympia to worldwide fame. As the United States expanded its empire abroad at the turn of the twentieth century, the ship became a source and symbol of national power.

Illustration of Cdr. Dewey and Olympia crew at the Battle of Manila, May 1, 1898. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

After the Spanish-American War, Olympia returned to the United States to victorious welcome ceremonies and parades Congress even established a special medal for the officers and men present in Dewey’s squadron during the Battle of Manila Bay. The ship then saw service in the Caribbean and Mediterranean, and it served as a training ship for the United States Naval Academy, until being placed in reserve in 1909.

Olympia was reactivated for World War I but saw very limited service. It patrolled the waters off of New York and, during the Russian Civil War, landed in Murmansk, Russia to secure munitions that had been sent to aid Tsarist forces. From May 24, 1918 to November 11, 1918, Olympia cruised Russian waters and assisted U.S. efforts to aid anti-Bolshevik forces on land. In 1919, the ship served in the Mediterranean and Black Seas and observed the Turkish War of Independence. Olympia ended 1920 by rescuing refugees trapped in the Crimean peninsula as they fled the Bolsheviks.

When the call came to honor an Unknown Soldier from World War I, Secretary of War Newton Baker inquired what it would cost the Navy to participate in the ceremonies. Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels replied, at the end of January 1921, that “it would be entirely convenient for me to order the OLYMPIA, now in the Adriatic, to bring the body to America it would be most fitting and appropriate that the body of this unidentified soldier or marine should be brought to America in this ship which holds a unique place in American history and was the flagship of Admiral Dewey at the time he won the battle of Manila.” Daniels went on to say that the cost of this plan would be negligible.

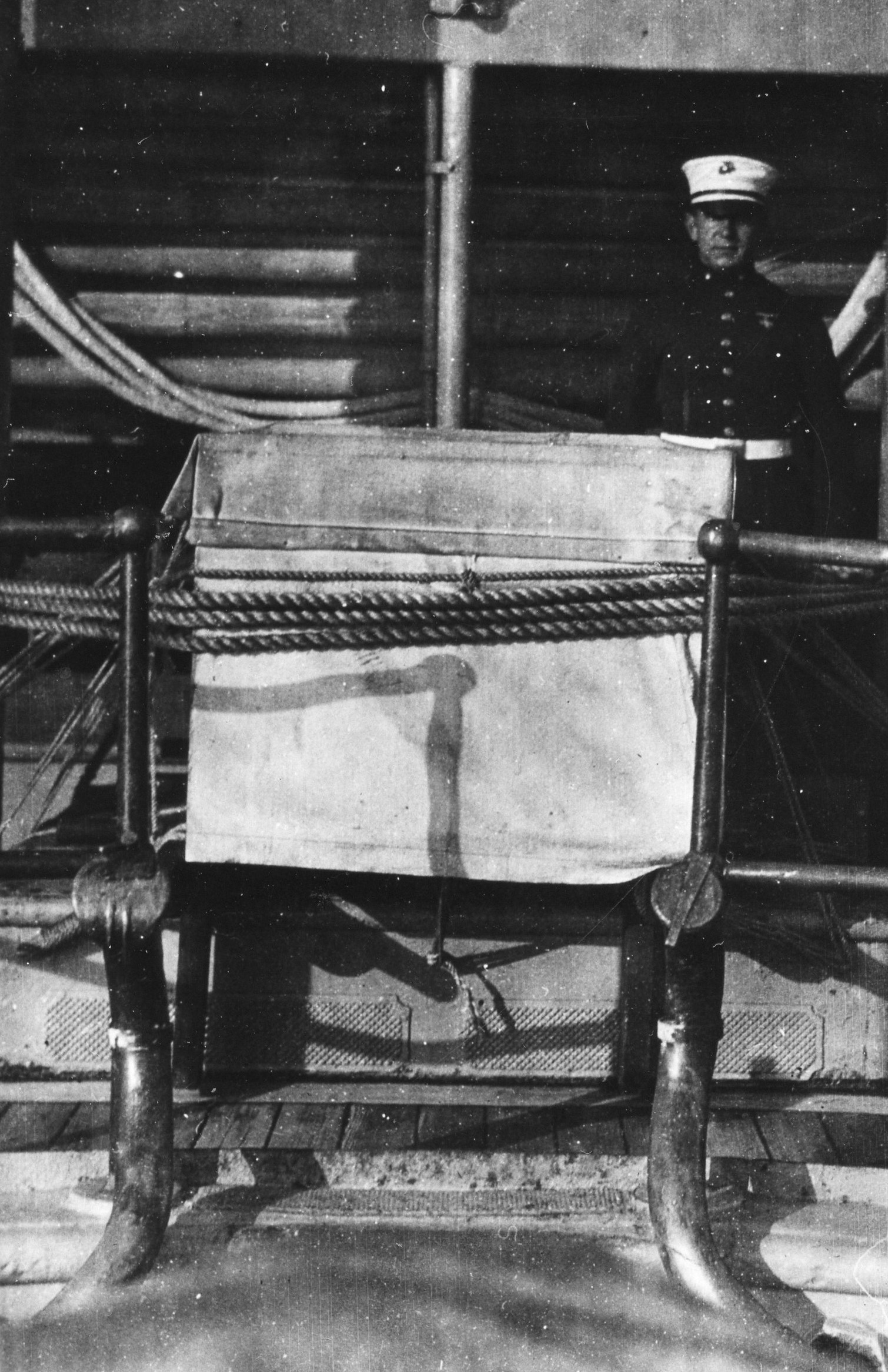

On October 3, 1921, Olympia sailed to Le Havre, France to transport the Unknown Soldier home. Olympia briefly stopped in Plymouth, England and sent twenty five officers and fifty men to London to participate in the October 17 ceremonies honoring the Unknown Warrior with the U.S. Medal of Honor, eventually arriving in France on October 24. The next day, the Unknown Soldier arrived in Le Havre and was taken aboard Olympia after speeches and honors from French and American officials. Escorted out of Le Havre by USS Reuben James (DD-245), six French destroyers and eight French torpedo boats, Olympia sailed home. It had a challenging journey due to weather. Throughout the voyage, Marines guarded the casket, which had been lashed to the deck to prevent loss during rough seas.

On October 3, 1921, Olympia sailed to Le Havre, France to transport the Unknown Soldier home. Olympia briefly stopped in Plymouth, England and sent twenty five officers and fifty men to London to participate in the October 17 ceremonies honoring the Unknown Warrior with the U.S. Medal of Honor, eventually arriving in France on October 24. The next day, the Unknown Soldier arrived in Le Havre and was taken aboard Olympia after speeches and honors from French and American officials. Escorted out of Le Havre by USS Reuben James (DD-245), six French destroyers and eight French torpedo boats, Olympia sailed home. It had a challenging journey due to weather. Throughout the voyage, Marines guarded the casket, which had been lashed to the deck to prevent loss during rough seas.

The Unknown Soldier's casket lashed to Olympia's deck. (National Archives)

After its difficult transatlantic voyage, Olympia finally sailed up the Potomac River and docked at the Washington Navy Yard on November 9 around 3:01 P.M. Navy and Marine Corps body bearers carried the casket to the gangplank while the cruiser fired 21 minute guns and the band played Chopin’s “Funeral March." The boatswain piped the Unknown ashore in the presence of Generals John J. Pershing and John A. Lejeune, Secretary of War John Weeks, Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby and other dignitaries. Olympia’s honor guard turned over the flag-draped casket to eight Army body bearers, who placed it on a caisson. The 3rd Cavalry band played “Onward Christian Soldiers,” and the caisson proceeded to the Capitol.

Sailors and Marines carry the Unknown's casket, Washington Navy Yard, November 9, 1921. (National Archives)

Olympia concluded its distinguished military service, with appropriate ceremony and symbolism, by bringing home the Unknown Soldier of World War I. Like Memorial Amphitheater—whose inscriptions include the names of Spanish-American War generals, admirals, and battles—the ship “link[ed] the Unknown of the Great War to the Spanish-American War and the Philippines,” as historian Micki McElya has written. It not only transported the Unknown’s body, but also situated his sacrifice within a longer history of American military engagements. Furthermore, as the first war in which the United States repatriated the remains of fallen service members, the Spanish-American War held significance as a historical precedent for the Unknown’s return home.

Although Olympia continued to serve for over one more year, the return of the Unknown Soldier was its last major mission. The Navy decommissioned Olympia on December 9, 1922, but the famous ship went on exhibit during the Philadelphia Sesquicentennial in 1926. It was designated as an unclassified miscellaneous auxiliary (IX-40) in 1931. In January 1957, the Navy declared the ship unfit for naval service, struck it from the Naval Register, and transferred it to the Cruiser Olympia Association.

USS Olympia at the Independence Seaport Museum. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

In 1976, Olympia was designated a National Historic Landmark, and in 1996, the Independence Seaport Museum in Philadelphia took responsibility for its care. Today, Olympia serves as a museum ship and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

As we commemorate the Navy's birthday and the centennial of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, we honor Olympia and all U.S. sailors who served during the Unknown's voyage and ceremonies. In World War I as in other wars, the Navy lost many sailors at sea, their bodies unidentifiable. USS Olympia embodies their memory and legacy.

To Learn More

Explore our Education Program modules, featuring lesson plans, primary-source readings, walking tours and more:

► The Spanish-American War

► The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

Selected Sources Consulted

• ANC Historical Research Collection, Box 12.

• Historical Naval Ships Association, “USS Olympia (C-6),” https://www.hnsa.org/hnsa-ships/uss-olympia-c-6/.

• Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC), “Olympia I (Cruiser No. 6),” https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/o/olympia.html.

• McElya, Micki. The Politics of Mourning: Death and Honor in Arlington National Cemetery. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

• Mossman, B.C. and M.W. Stark. The Last Salute: Civil and Military Funerals, 1921-1969. Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1991.

• USS Olympia Deck Log, 1/1/1921–12/31/1921, Record Group 24 (Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel), National Archives and Records Administration; digitized version at https://catalog.archives.gov/id/148844639.