Ida Lewis, the namesake of Arlington National Cemetery’s Lewis Drive, was once known as “the bravest woman in America.” Lewis served as an official lighthouse keeper for the U.S. Lighthouse Service (later absorbed into the Coast Guard) from 1879 until her death, at age 69, in 1911. As the keeper of Lime Rock Light Station off the coast of Newport, Rhode Island, Lewis performed work that was critical to national security: lighthouses, administered by the federal government, aided navigation and helped protect the nation’s coastlines.

Ida Lewis, the namesake of Arlington National Cemetery’s Lewis Drive, was once known as “the bravest woman in America.” Lewis served as an official lighthouse keeper for the U.S. Lighthouse Service (later absorbed into the Coast Guard) from 1879 until her death, at age 69, in 1911. As the keeper of Lime Rock Light Station off the coast of Newport, Rhode Island, Lewis performed work that was critical to national security: lighthouses, administered by the federal government, aided navigation and helped protect the nation’s coastlines.

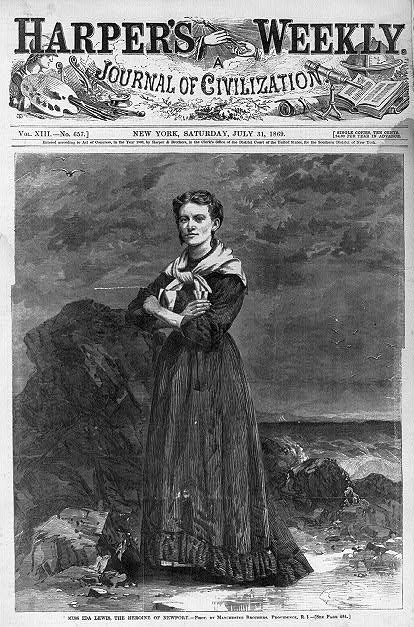

Right: Ida Lewis, ca. 1869. (U.S. Coast Guard)

Lewis also performed personal acts of heroism by rescuing people from drowning in the turbulent, cold waters off Newport. According to Coast Guard records, Lewis saved the lives of 18 people, including several soldiers from nearby Fort Adams; unofficial accounts hold that she saved as many as 36. Until 2020, she was the only woman to receive the Coast Guard’s Gold Lifesaving Medal, the nation’s highest lifesaving decoration.

When ANC dedicated its 27-acre Millennium site in 2018, Lewis became the first woman honored with a road in the cemetery named for her. Ida Lewis Drive runs between Section 29 and Sections 77–84, the new sections created with ANC’s Millennium Project expansion, in the northwest of the cemetery. Lewis herself is buried at Island Cemetery in her birthplace of Newport, near the lighthouse she once managed.

Ida Lewis Rock Light, formerly the Lime Rock Light Station, Newport, Rhode Island. (U.S. Coast Guard)

Idawalley (Ida) Zoradia Lewis was born on February 25, 1842, the eldest of four surviving siblings. Her father, Captain Hosea Lewis, served in the Revenue Cutter Service — predecessor of the Coast Guard — which appointed him to guard the Lime Rock Light Station in 1853. Built on a small, rocky island in Newport Harbor, the lighthouse facilitated the safe passage of ferries and commercial ships, as well as vessels transporting military personnel to and from Fort Adams. In 1857, Hosea Lewis suffered a debilitating stroke, and his wife, Zoradia, became the lighthouse keeper. However, since Zoradia also had to care for her ailing husband and younger children, the teenaged Ida helped her mother with lighthouse duties. These included filling the lamp with oil at sundown and midnight, extinguishing the light in the morning, trimming the lamp’s wick, and rowing between the island and the mainland for supplies.

Lighthouse keeping was one of the few non-clerical federal jobs open to women in the 19th century. The Lighthouse Service, established in 1789 as part of Congress’s first Public Works Act, was originally overseen by the Treasury Department; it merged into the Coast Guard in 1939. No official policies prevented women from being lighthouse keepers, although most, like Zoradia Lewis, were appointed after the death or incapacity of their husbands. Between 1828 and 1905, at least 122 women held the official government position of lighthouse keeper. Because their duties — lighting the lamp, patiently watching the coastline, maintaining the lighthouse itself — appeared non-martial and even “domestic,” women could serve as lighthouse keepers without seeming to disrupt traditional notions of femininity. Yet Ida Lewis’s life reveals a more complex story.

Well before her official 1879 appointment as keeper of Lime Rock, Lewis had earned renown for her daring feats. A highly skilled rower and swimmer, Lewis reportedly performed her first rescue as a teenager, in the fall of 1858, when she rowed out to save four young men after their sailboat capsized in Newport Harbor. Her most famous rescue, on the stormy night of March 29, 1869, saved the lives of two Army soldiers whose boat had capsized as they sailed back to Fort Adams following an evening in Newport. When her mother spotted the soldiers clinging to their overturned boat, Ida went down to the shore, rowed through icy water and pulled the two men into her own boat. (A boy the soldiers had hired as a guide had already drowned.) For this courageous feat, Lewis received several medals, and President Ulysses S. Grant visited Lime Rock to meet Newport's heroine.

Well before her official 1879 appointment as keeper of Lime Rock, Lewis had earned renown for her daring feats. A highly skilled rower and swimmer, Lewis reportedly performed her first rescue as a teenager, in the fall of 1858, when she rowed out to save four young men after their sailboat capsized in Newport Harbor. Her most famous rescue, on the stormy night of March 29, 1869, saved the lives of two Army soldiers whose boat had capsized as they sailed back to Fort Adams following an evening in Newport. When her mother spotted the soldiers clinging to their overturned boat, Ida went down to the shore, rowed through icy water and pulled the two men into her own boat. (A boy the soldiers had hired as a guide had already drowned.) For this courageous feat, Lewis received several medals, and President Ulysses S. Grant visited Lime Rock to meet Newport's heroine.

Left: "Miss Ida Lewis, the Heroine of Newport." Harper's Weekly, July 31, 1869. (Library of Congress)

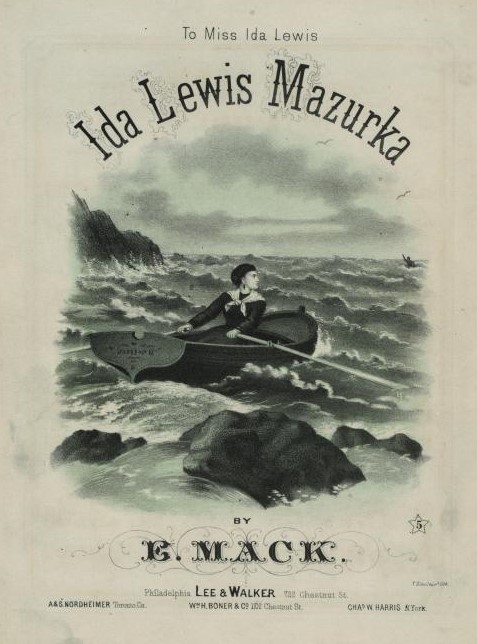

Covered in newspapers throughout the nation, Ida Lewis’s March 1869 rescue made her an overnight celebrity. New technologies of mass communication enabled the thrilling story — and, importantly, Lewis’s image — to be circulated across the nation. That spring and summer, she appeared in hundreds of local newspapers, which could receive faraway news via telegraph; on the covers of national magazines such as Harper’s Weekly; in photographs reprinted on mass-produced postcards and calling cards; and even in songs, like “The Ida Lewis Mazurka” and the "Rescue Polka Mazurka," that were popularized through illustrated sheet music. The town of Newport designated July 4, 1869, as “Ida Lewis Day” and sponsored a parade in its heroine’s honor, at which spectators could purchase Ida Lewis-themed hats, ties and other collectibles.

Covered in newspapers throughout the nation, Ida Lewis’s March 1869 rescue made her an overnight celebrity. New technologies of mass communication enabled the thrilling story — and, importantly, Lewis’s image — to be circulated across the nation. That spring and summer, she appeared in hundreds of local newspapers, which could receive faraway news via telegraph; on the covers of national magazines such as Harper’s Weekly; in photographs reprinted on mass-produced postcards and calling cards; and even in songs, like “The Ida Lewis Mazurka” and the "Rescue Polka Mazurka," that were popularized through illustrated sheet music. The town of Newport designated July 4, 1869, as “Ida Lewis Day” and sponsored a parade in its heroine’s honor, at which spectators could purchase Ida Lewis-themed hats, ties and other collectibles.

Right: Sheet music, 1869. (New York Public Library)

Ida Lewis’s fame, and the public’s eager consumption of her image, both affirmed and challenged prevailing cultural ideas about gender. On the one hand, she could be construed as a distinctly “feminine” type of hero: one who risked her life in order to save others. The most popular photograph of her — copies of which Lewis herself signed and gave to fans — depicted her holding an oar, but wearing a fine dress and jewelry; her clothing looks unsuited to actually using the oar. Yet, as one scholar has argued, Lewis’s pose and attire “served a different function: underscoring her propriety and traditional femininity.” Such depictions extended to female lighthouse keepers generally, who were lauded in 19th-century American culture as heroic yet nonetheless “proper” white, middle-class women. Indeed, other widely circulated images (including illustrations for the Harper’s Weekly cover story on Lewis) portrayed lighthouses as houses, in which female keepers performed traditional domestic work.

"Interior of Lime Rock LIght-House—Ida Lewis at Home."

Wood engraving printed in Harper's Weekly cover story, July 31, 1869. (Library of Congress)

On the other hand, Ida Lewis's well-publicized rescues proved that lighthouse keeping entailed far more than the placid scene pictured above. The women’s rights movement had gained momentum in the years following the Civil War, and in this context, narratives about “the bravest woman in America” (as the press dubbed Lewis) could also support demands for suffrage and equality. Shortly after the Ida Lewis Day parade on July 4, 1869, two of the nation’s leading suffragists, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, visited Lewis at Lime Rock; Stanton purchased a photograph of her, which she reportedly displayed in her office. Although there seems to be no evidence that Lewis herself publicly advocated voting rights, her actions emphatically demonstrated that women could be strong, courageous and capable — and thus deserving of suffrage and other citizenship rights. Moreover, by serving as lighthouse keepers, women such as Lewis made key contributions to national security — and, at times, saved the lives of military personnel — long before they were officially allowed to enlist in the military.

When the Lighthouse Service designated Ida Lewis as the keeper of Lime Rock Lime Station in 1879, it formalized responsibilities that she had been undertaking, voluntarily and unofficially, for over a decade. She eventually became the highest-paid lighthouse keeper in the nation, earning $750 per year. Lewis received the Gold Lifesaving Medal in 1881, for rescuing two Fort Adams soldiers who fell through thin ice while attempting to walk across the frozen harbor. Her numerous other awards included a monthly “hero” pension from Andrew Carnegie, the steel magnate and philanthropist. Lewis performed her last rescue when she was in her sixties. She died on October 24, 1911, following a stroke while on duty.

In 1924, the Lighthouse Service changed the name of Lime Rock Light Station to Ida Lewis Rock Light Station. More than a hundred years after her death, Arlington National Cemetery's naming of Lewis Drive continues to honor her legacy. The next time you visit the cemetery, take a walk down Lewis Drive and reflect upon the many ways that American women have served their nation from outside the official ranks of the military.

Lewis Drive is between Section 29 and Sections 77–84 of Arlington National Cemetery. (Jenifer Van Vleck)

Selected Sources

• Margaret C. Adler, “To the Rescue: Picturing Ida Lewis.” Winterthur Portfolio 48, no. 1 (2014): 75–104; quote, p. 85. https://doi.org/10.1086/676321.

• Candace Clifford, “Celebrating Ida Lewis.” United States Lighthouse Society, February 25, 2017.

• Craig Collins, “Always Ready: Women’s Crucial Role in the U.S. Coast Guard.” Defense Media Network, May 16, 2018.

• Newport Historical Society, “History Bytes: Ida Lewis.” April 21, 2020.

• New England Historical Society, “Ida Lewis, The Bravest Woman in America.” Undated (accessed March 18, 2022).

• Amanda Shields, “Ida Lewis: Mother of All Keepers.” Mariners’ Blog, The Mariners’ Museum and Park, March 22, 2021.

• William H. Thiesen, “Remembering Ida Lewis, the ‘Bravest Woman in America.’” The Maritime Executive, March 23, 2017.

• United States Coast Guard, “Notable People: Idawalley Zorada Lewis(-Wilson), Keeper, USLHS.”

• United States Coast Guard, “Breaking the Barrier: Women Lighthouse Keepers and Other Female Employees of the U.S. Lighthouse Board/Service.” Undated (accessed March 18, 2022).

• Wayne Wheeler, “History of the Administration of the Lighthouses in America.” United States Lighthouse Society website, undated (accessed March 18, 2022).