Grave of Maj. David F. Cole, 107th United States Colored Troops. (Douglas Breton)

Every day, visitors to Arlington House, a National Park Service site located within Arlington National Cemetery, pass a row of 50 headstones lining the path around the flower garden. Located within the boundaries of Arlington National Cemetery, these are the graves of U.S. Army officers who died during the Civil War. Most of the headstones are uniform in size and shape, all made of white marble. One however, stands much taller than any other. This privately purchased headstone often catches visitors’ attention. Those who stop to read it will find a short inscription: “D. F. Cole, Major of the 107th Col’d Infy. Died at Point of Rocks, Va., Jan. 7, 1865, aged 27 years – FLORENCE.” This is much more information than most Civil War grave markers provide. Yet it raises more questions than it answers. Who was Major D. F. Cole, and why was he buried so close to Arlington House with a privately furnished marker instead of a government-issued headstone?

David Farnum Cole was born in Grafton, New Hampshire, on May 22, 1836. His father was a farmer who, in 1850, owned land worth $1,800. Despite being wealthier than their neighbors, with seven children the Cole family’s resources were spread thin. David F. Cole grew up with limited schooling. When he enrolled in nearby Dartmouth College, his lack of preparation and meager finances led to numerous struggles. Nevertheless, he was determined to obtain the education he needed to advance in life. Through dedication to his work, he graduated near the top of his class and became a member of the Phi Beta Kappa honor society.

The excitement and anxiety that Dartmouth’s class of 1861 probably experienced grew even greater due to the timing of their graduation. The college held its commencement ceremony on July 25, 1861, three months after the outbreak of the Civil War. The conflict was on everyone’s mind. Both the ceremony’s keynote speaker and the poet who followed him delivered fiery addresses denouncing slavery and secession while calling for the preservation of the Constitution and the Union. Some of the graduates who soon enlisted in the U.S. Army may have found these words inspirational. At first, however, Cole did not pursue military service. Perhaps needing to earn income, he instead became the headmaster of Chelsea Academy in Chelsea, Vermont. As the new year started, it is likely that his main concern was preparing the school for the next term.

The following summer, everything changed. When the U.S. Army’s Peninsula Campaign failed to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, President Abraham Lincoln called for 300,000 new soldiers to enlist for nine months. Cole finally decided to take a stand. On Aug. 22, 1862, at the age of 26, he commissioned into the United States Army. His service records contain the only surviving description of his physical appearance. He was 5 feet 9 inches tall with a light complexion, blue eyes, and dark hair. A tintype produced sometime afterward is his only known photograph.

The following summer, everything changed. When the U.S. Army’s Peninsula Campaign failed to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, President Abraham Lincoln called for 300,000 new soldiers to enlist for nine months. Cole finally decided to take a stand. On Aug. 22, 1862, at the age of 26, he commissioned into the United States Army. His service records contain the only surviving description of his physical appearance. He was 5 feet 9 inches tall with a light complexion, blue eyes, and dark hair. A tintype produced sometime afterward is his only known photograph.

Tintype of Capt. David F. Cole, 12th Vermont Infantry. (Vermont Historical Society)

As a captain, Cole helped to recruit men for Company D of the 12th Vermont Infantry. Once filled, the regiment joined the Second Vermont Brigade in Washington, D.C., spending the winter in camps throughout Northern Virginia. The brigade’s soldiers soon gained an appreciation for Capt. Cole’s leadership and generosity. In December 1862, they traveled through a heavy snowstorm near Alexandria, Virginia. Lt. Edwin F. Palmer, who had graduated from Dartmouth one year after Cole, noticed that six men in his own regiment, were suffering heavily from the effects of the storm. He went to his college friend and asked for help. The 12th Vermont had already finished preparing their barracks; after securing approval from the chief cook, Cole sheltered them in the cooking shanty. Two years later, Palmer recalled his gratitude. “Never was hospitality more freely given by knights or king in royal palace, or more thankfully received, than in that rough shanty in the woods of Virginia.”

Before long, however, Cole’s promising military career almost came to a premature end. The Second Vermont Brigade’s new commander, Brig. Gen. Edwin Stoughton, took an instant dislike to Capt. Cole. Accusing him of neglecting his duties, he placed him under arrest that Christmas. Though released five days later, Cole was ordered to appear before a military board in mid-January. The men of the 12th Vermont waited apprehensively. Would their beloved commander lose his commission over these charges?

After careful and thorough deliberation, on Jan. 20, 1863, the board concluded that Cole was “remarkably well instructed in all the duties of his profession; that his answers to the various questions were most satisfactorily, and that his explanations of the different movements were clear and precise.” It also found him “in all respects fully qualified for the position he now holds.” Newspapers in Vermont triumphantly proclaimed the news. To show their gratitude, Cole’s soldiers pooled their money together and formally presented him with an expensive military hat. Less than two months later, Confederate guerillas captured Gen. Stoughton at Fairfax Courthouse, Virginia. After he was exchanged, he never held another military command.

The 12th Vermont spent most of its nine months in military service guarding railroads in northern Virginia, occasionally engaging in brief clashes with Confederate partisans. The closest they ever came to seeing a major battle was in the summer of 1863, when they marched along the hot, muddy roads to Gettysburg, their poorly made shoes falling apart along the way. Although three of the Second Vermont Brigade’s regiments fought in the battle, flanking Pickett’s Charge on the final day, the 12th Vermont remained far to the rear, guarding ammunition trains. They ended their nine months of service without ever participating in a significant battle.

David F. Cole mustered out of service on July 14, 1863. He attempted to reenlist veterans in a new regiment but only found thirty willing volunteers from his old company. For the moment, his time in the Army was over. Turning his attention to resuming his civilian career, he moved to Cleveland that September and began to study law under Albert Gallatin Riddle, a former Ohio congressman who had concluded his term the previous March. It was an auspicious start for a recent college graduate. Even so, he was dissatisfied. As one newspaper later eulogized, “His love of Country however would not permit him to remain in civil life.” Therefore, he made another bold decision, one that may have been inspired by his new mentor.

In January 1862, Albert G. Riddle had given a speech in the House of Representatives calling for enslaved African Americans to enlist in the U.S. military—a proposal so controversial that one representative asked in a shocked reply, “Does he contend that the Federal Government has a right to enlist slaves in the Army of the United States?” Now, this had finally become a reality. African American men were joining the U.S. Army through the United States Colored Troops (USCT). However, due to racist beliefs within the military and the civilian government, they were not allowed to serve as officers. Only white men could receive commissions. Believing that Black men would make good soldiers, Cole determined to become an officer in a USCT regiment. In early 1864, he passed his examination to become a major and recommissioned into the U.S. Army.

In uniform once again, Cole traveled to Kentucky to recruit soldiers for the 107th USCT. There, he encountered strong opposition to his efforts. Although Kentucky was still in the Union, its laws also permitted the enslavement of African Americans. In February 1864, the governor wrote directly to President Lincoln to protest efforts to raise USCT units in his state. While conceding the necessity of enlisting Black soldiers in rebellious states, he quoted the state’s laws to warn that if military officers should “enlist a slave or ‘entice or persuade a slave to leave his master or owner’ and enlist in a ‘colored troop,’” they could be imprisoned for between two and 20 years. Undeterred, Lincoln allowed the enlistments to proceed. By the end of the war, Kentucky, home to just five percent of the country’s Black population, produced 13 percent of all USCT soldiers.

The men who joined the 107th USCT put their lives on the line for the cause of freedom. Nearly two years earlier, just before the Emancipation Proclamation took effect, Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered that any Black soldiers who were captured with weapons should be handed over to civilian authorities and “be dealt with according to the laws of said States.” The same would be done “with respect to all commissioned officers of the United States when found serving in company with armed slaves in insurrection against the authorities of the different States of this Confederacy.” According to the laws of these states, the officers in question could be put to death.

Cole surely knew the risks, as did the men he recruited. Several weeks after mustering into service, Cole drafted his last will. In it, he appointed his former employer, Albert G. Riddle, as executor. Aside from his papers, which he wanted sent to his father, he left everything he owned—real estate, personal property, money and personal effects—to his “dear friend Florence Riddle oldest daughter of Hon. A. G. Riddle.” No correspondence has surfaced to reveal the full nature of their relationship. Nevertheless, considering that she was the only beneficiary he listed besides his father and sister, it is possible that they were more than merely friends.

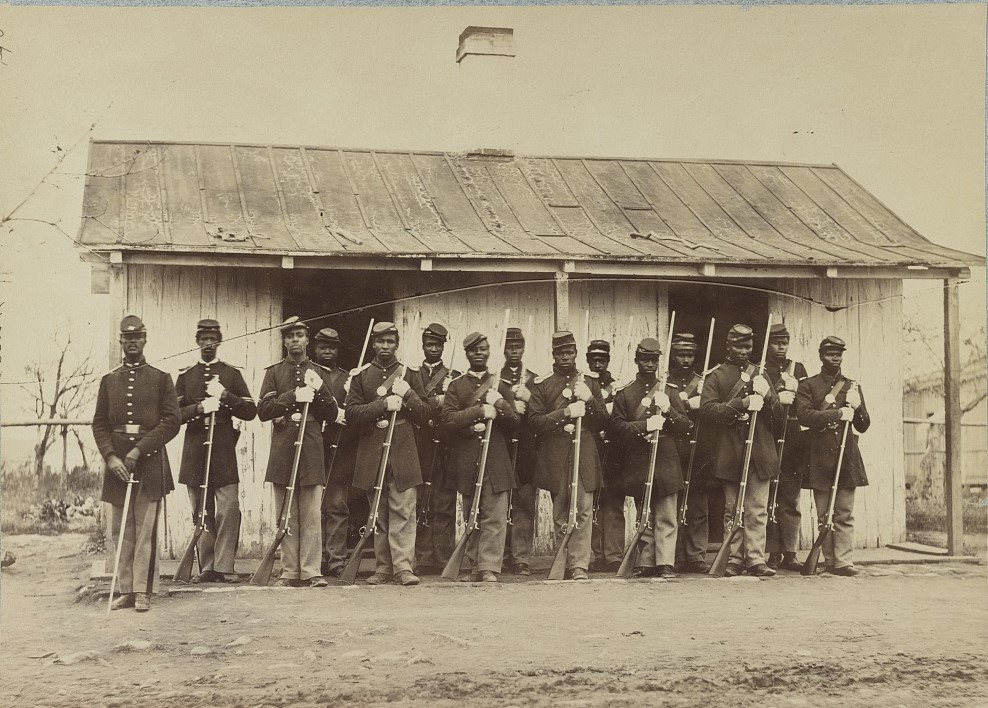

Soldiers in the 107th USCT at Fort Corocoran (modern-day Rosslyn, VA), November 1865. (Library of Congress)

The 107th USCT remained in Kentucky until October 1864, when it traveled to Baltimore and then City Point, Virginia, Ulysses S. Grant’s base of operations during the Siege of Petersburg. The regiment remained there for only a month before traveling to North Carolina. There, it helped capture Fort Fisher and the city of Wilmington, the Confederacy’s last major port. Cole, however, would not join them. On Dec. 1, 1864, he developed typhoid fever and was sent to the hospital in Point of Rocks, Virginia. Typhoid and malaria (which doctors frequently did not distinguish from one another, including in Cole’s case) took more lives in the Civil War than any other disease except dysentery. That winter, many soldiers succumbed to these diseases. As Annie Wittenmyer of the United States Christian Commission wrote, “The hospitals were overcrowded at City Point and Point of Rocks. Every cot was occupied, every tent was crowded, and the thousands of troops coming down quartered wherever they could find a vacant place.” After a month of hospitalization, Cole’s condition deteriorated. On Jan. 7, 1865, he died from his illness. He was just 28 years old.

General Hospital at Point of Rocks, VA. (Library of Congress)

Like the hundreds of soldiers who died every day during the Civil War, Cole’s story may have ended as just a few lines in an impersonal government document. But many soldiers loved him, and they worked to ensure that he would be remembered. On the same day that the Army made a final inventory of his few possessions, the officers of the 107th USCT produced a resolution honoring him. It was printed in at least three different newspapers.

A more lasting tribute followed soon afterward. One of Major Cole’s final requests was that he should be buried at Arlington National Cemetery. To many, the new national cemetery was not a place of honor. Families regularly requested that their loved ones be disinterred and sent home. Yet Cole saw it differently. In accordance with his wishes, his body was transported to the home of his former employer, Albert G. Riddle, on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. On Jan. 13, 1865, a procession took Cole to his final resting place at Arlington. An article in the Cleveland Morning Leader described the solemn event:

It was a beautiful winter day when the funeral cortege left the residence of Hon. A.G. Riddle, crossed the Long Bridge, and winding up the ascent of Arlington Heights, halted at the door of the mansion, covered with the national ensign; and in the adjoining parlor the simple but impressive service of the Methodist Episcopal church was conducted. The emotions which consecrated that occasion were shared by none more fully then by several of the college friends of the deceased, who were present. We consigned him to a soldier’s grave, and left him, not “alone in his glory,” for an army of his brave compatriots lie near him, but with the consolatory knowledge that as his military career had been glorious and unsullied by a bad act, his death was the last and greatest of his victories.

Newspapers in all four states where Cole had lived printed loving tributes to him. All praised his patriotism and deep religious convictions. As one stated, “When a man like David F. Cole dies, his death should be mourned not alone by friends and acquaintances, but by all loyal hearts. It is a loss to the Republic.”

Two men looking at David F. Cole's grave, with Arlington House's portico in the background. Undated. (Virginia Museum of History and Culture)

At that time, almost all of Arlington National Cemetery’s graves were marked with simple white headboards bearing whatever details were known about the soldiers interred there. Those who knew Cole decided that he needed a more lasting memorial. Shortly after the funeral, one newspaper declared, “A monument is soon to be erected by the officers and men of his regiment, over his grave, on the terrace near Arlington House. The spot is a beautiful one, in full view of the Capitol and the broad expanse of the river, whose bright waters as they flow by him will sing his perpetual requiem.” Perhaps they were the ones who purchased this headstone.

Eight years after the Civil War ended, a Louisiana journalist who was visiting Arlington House told a more romantic story about Cole’s grave. The reporter passed the graves of the 48 officers then buried at Arlington National Cemetery, noting that “The highest in rank is Maj. D. F. Cole, of the 107th Colored Infantry.” He recorded the inscription on the “handsome monument” for his readers and commented, “This monument was erected to his memory by a young lady to whom he was betrothed.” With the name “Florence” carved in large letters at its base, it is quite possible that Florence Riddle loved him enough to leave a lasting tribute to his memory.

Most of the Civil War casualties buried in Arlington National Cemetery, including some of Cole’s own soldiers, never had their stories recorded. For thousands of them, even their names are unknown. In Cole’s case, the devotion of his friends and loved ones preserved their memories of him one hundred and sixty years later. But even when these stories and names are lost, the effects of their service are still felt today. Their sacrifices brought freedom to four million people and helped reunite the nation. Those who visit their graves can continue to gain inspiration from them to this day.

Selected Sources

“Arlington House and the National Cemetery – A Tribute to Major David F. Cole.” Cleveland Morning Leader. January 22, 1865.

Benedict, G. G. Army Life in Virginia: Letters from the Twelfth Vermont Regiment. Burlington, Vt: Free Press Association, 1895.

Benedict, G. G. Vermont in the Civil War: A History of the Part Taken by the Vermont Soldiers and Sailors in the War for the Union, 1861-65, Vol. 2. Burlington, Vt.: The Free Press Association, 1888.

Berlin, Ira, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland, eds. Freedom’s Soldiers: The Black Military Experience in the Civil War. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Chapman, George Thomas. Sketches of the Alumni of Dartmouth College. Cambridge, Mass.: Riverside Press, 1867.

The Daily Green Mountain Freeman (Montpelier, Vt.). March 2, 1862.

“Death of Major D. F. Cole.” Burlington Free Press (Burlington, Vt.). January 20, 1865.

“Death of Major David F. Cole.” Cleveland Morning Leader. February 1, 1865.

Dyer, Frederick H. A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion. Des Moines, Iowa: Dyer Publishing Company, 1908.

Glatthaar, Joseph T. Forged in Battle: The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers. Baton Rouge, La.: Louisiana State University Press, 1990.

Military, Compiled Service Records. Civil War. Carded Records, Volunteer Organizations. Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1890–1912, Record Group 94. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

“Our Washington Letter.” Donaldsonville Chief (Donaldsonville, La.). June 7, 1873.

Palmer, Edwin Franklin. The Second Brigade: Or, Camp Life. Montpelier, Vt: E.P. Walton, 1864.

Peck, Theodore S. Revised Roster of Vermont Volunteers Who Served in the Army and Navy of the United States during the War of the Rebellion, 1861-66. Montpelier, Vt.: Press of the Watchman, 1892.

Learn More

• Education Program: The Civil War Era