Tomb of the Unknown Soldier Centennial Commemoration Lecture Series

Leadership, the Lost Battalion, and the Burden of Heroism

Written and presented by Dr. Frank A. Blazich, Jr., Curator, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

This episode explores the Lost Battalion's epic fight in the Argonne forest during World War I, its two leaders, Maj. Charles W. Whittlesey and Capt. George G. McMurtry, and their connections with the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

Listen Here: Leadership, the Lost Battalion, and the Burden of Heroism

Dr. Frank A. Blazich, Jr. is a curator of modern military history at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History. He earned his Ph.D. from The Ohio State University in 2013 and worked for the United States Navy prior to coming to the Smithsonian. He is the editor of Bataan Survivor: A POW's Account of Japanese Captivity in World War II, and author of ‘An Honorable Place in American Air Power’: Civil Air Patrol Coastal Patrol Operations, 1942-1943.

Learn More:

View the official military personnel file of Charles Whittlesey here.

Cher Ami, the famous homing pigeon, is preserved as part of the collection at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Read more about Cher Ami here.

Read more about the history homing pigeons during World War I here.

Major Charles W. Whittlesey, commander of the first battalion of the 308th Infantry Regiment and commander of the composite force known as the “Lost Battalion.” For his heroic leadership during the ordeal of the unit, Whittlesey received the Medal of Honor and became a national hero, but the experience haunted him until he took his own life in 1921. U.S. Army Signal Corps photo from October 29, 1918. (National Archives)

Major Charles W. Whittlesey, commander of the first battalion of the 308th Infantry Regiment and commander of the composite force known as the “Lost Battalion.” For his heroic leadership during the ordeal of the unit, Whittlesey received the Medal of Honor and became a national hero, but the experience haunted him until he took his own life in 1921. U.S. Army Signal Corps photo from October 29, 1918. (National Archives)

Major George G. McMurtry, commander of the second battalion of the 308th Infantry Regiment, and second in command of the Lost Battalion. A recipient of the Medal of Honor, he is seen here on arriving back to the United States with members of the 77th Division in April 1919. U.S. Army Signal Corps by Lt George H. Lyon. (National Archives)

Major George G. McMurtry, commander of the second battalion of the 308th Infantry Regiment, and second in command of the Lost Battalion. A recipient of the Medal of Honor, he is seen here on arriving back to the United States with members of the 77th Division in April 1919. U.S. Army Signal Corps by Lt George H. Lyon. (National Archives)

View from Hill No. 198 looking into the Charlevaux Ravine on the north hillside where the Lost Battalion held its position, or “pocket,” while besieged by German forces for over five days. Just below the white cliff edge is the Lost Battalion’s objective: the Binarville-La Viergette Road. U.S. Army Signal Corps photo from November 22, 1918. (National Archives)

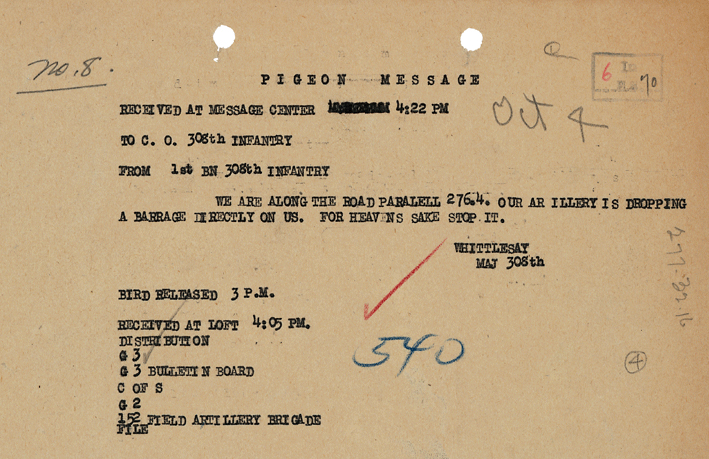

Transcribed message sent by homing pigeon from Major Charles Whittlesey, commanding the first battalion on the afternoon of October 4, 1918, to Colonel Cromwell Stacey, commanding officer of the 308th Infantry Regiment, requesting urgent relief from incoming friendly artillery fire. (National Archives)

Survivors and “walking wounded” of the Lost Battalion. Of the nearly 700 men who entered the Charlevaux Ravine between 2 to 7 October 1918, only 194 walked out under their own power, a casualty rate of over 70 percent. U.S. Army Signal Corps photo from October 29, 1918. (National Archives)

Recommended readings:

-

Finding the Lost Battalion. Website related to Robert J. Laplander, Finding the Lost Battalion: Beyond the Rumors, Myths, and Legends of America's Famous WWI Epic (Lulu.com, 2017).

-

World War I Centennial Commission, "Lost Battalion."

-

Charles White Whittlesey Collection, Williams College Archives & Special Collections.

-

Official Military Personnel File of Charles Whittlesey, National Archives and Records Administration.

-

Charles Lee McCollum, History and Rhymes of the Lost Battalion (Chicago: Foley and Company Printers, 1922), HathiTrust Digital Library.

-

Film, "The Lost Battalion" (dir. Burton King, W.H. Productions Co., 1919), Library of Congress.

-

L. Wardlaw Miles, History of the 308th Infantry, 1917-1919 (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, The Knickerbocker Press, 1927), HathiTrust Digital Library.