Matthew Alexander Henson

On April 6, 1909, U.S. citizens Matthew Alexander Henson and Robert Edwin Peary, and four Inuit assistants, became the first human beings to set foot on the North Pole. Henson and Peary had been attempting to reach the Pole for the past 18 years. According to Henson, he was the first of the group to reach the North Pole.

Matthew Henson was born in Charles County, Maryland in 1866. His parents were sharecroppers, like many African Americans in the post-Civil War years. Both died during Henson's childhood. At the age of 12, he went to work as a cabin boy on a merchant ship, having been fascinated by stories of the sea. Aboard the ship for six years, he learned how to read, write and navigate. Later, while working as a clerk in a Washington, D.C. hat shop, he met Commander Robert E. Peary, who was planning a surveying expedition to Nicaragua. Upon learning of Henson's sailing and navigation experience, Peary hired him as a valet. On the 1888 Nicaragua expedition, Henson impressed Peary, and subsequently accompanied him on seven Arctic expeditions between 1891 and 1909.

In 1912, Henson published an account of his experiences, "A Negro Explorer at the North Pole," and he gave lectures throughout the country. Compared to Peary, however, he received relatively little immediate recognition for his part in the 1909 expedition to the North Pole. He spent the remainder of his career in obscurity, working as a clerk at the U.S. Customs House in New York City. Late in his life, Henson received some long-overdue honors: the prestigious Explorers Club finally admitted him as a member in 1937, Congress awarded him the Peary Polar Expedition Medal in 1944, and Presidents Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower welcomed him to the White House.

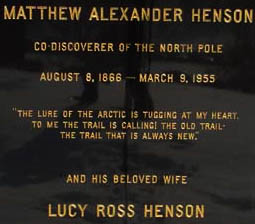

After his death in 1955, Matthew Henson was buried at New York's Woodlawn Cemetery. In 1987, at the request of Dr. S. Allen Counter of Harvard University—a neurobiologist, explorer and expert on Henson—President Ronald Reagan granted an exception to Arlington National Cemetery's burial policy, allowing for the bodies of Henson and his wife, Lucy Ross Henson, to be reinterred at Arlington with full military honors.

On April 6, 1988, the remains of Matthew Henson and his wife were transported to Washington, D.C., where they were buried near the gravesite of Admiral Peary and his wife, Josephine Deibitsch Peary. Members of Henson's family attended the ceremony, along with admirers from around the world. That same year, the National Geographic Society posthumously awarded Henson the Hubbard Medal, its highest honor. The reinterment and the medal represented the ultimate national recognition that Henson had so long deserved.

The monument on Henson's gravesite features an inset bronze plaque commemorating the North Pole discovery. At the top sits a large bas-relief bust of Henson in Arctic gear. Immediately below, an inscription describes his part in reaching the North Pole. Globes of the world, tilted with the Pole in view, sit at either side.

The central image — based on a photograph that Peary took at the Pole on April 6, 1909 — shows Henson flanked by the four Inuit assistants who accompanied the trip. The U.S. flag flies behind them atop a mound of ice.

The bottom panel, depicting dogsleds and dramatic ice floes, suggests the struggle that Henson, Peary and the Inuit sustained over many years to achieve their goal.

On the opposite side, an inscription quotes Henson's book, "A Negro Explorer at the North Pole": "The lure of the Arctic is tugging at my heart. To me the trail is calling! The old trail. The trail that is always new."