United States Air Force

A C-47 performs a flyover at the funeral of Maj. Gen. Marcelite Harris, February 7, 2019.

The United States Air Force (USAF) was established by the National Security Act of 1947, which took effect on September 18, 1947. In honor of the Air Force's 73rd birthday, read our blog post about the origins of the USAF, and scroll down to learn about the Air Force legacy at Arlington National Cemetery. This commemorative feature highlights 20 USAF service members who made history—but every Air Force gravesite at the cemetery honors those who served to support the USAF mission “to fly, fight and win… in air, space and cyberspace.”

Notable USAF Graves at Arlington National Cemetery

Lee "Buddy" Archer (1919-2010) — When Lee "Buddy" Archer enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1941, he wanted to become an aviator, but was initially rejected from pilot training on account of his race. A year later, however, he received acceptance to a new training program for Black pilots at the Tuskegee Army Airfield in Alabama. Graduating first in his class, he became one of the Tuskegee Airmen, assigned to the 302nd Fighter Squadron of the 332nd Fighter Group. During World War II, Archer flew 169 combat missions across 11 nations and earned the Distinguished Flying Cross. His most famed aerial combat mission occurred on October 12, 1944, when he shot down three German planes in ten minutes. Archer transitioned to the Air Force after its creation as a separate service branch in 1947, retiring in 1970 as a lieutenant colonel. (Section 6, Grave 9215 RH)

Henry H. "Hap" Arnold (1886-1950) — The only officer to hold a five-star rank in two different military services, and the only U.S. Air Force general to hold a five-star rank, Gen. Henry "Hap" Arnold was promoted to General of the Army on December 21, 1944 and became General of the U.S. Air Force on May 7, 1949. Taught to fly by the Wright brothers, Arnold was one of the first military pilots worldwide, and one of the first three rated pilots in the history of the U.S. Air Force. He supervised the expansion of the Army Air Service during World War I and, as a protegee of Gen. Billy Mitchell, continued promoting the development of air power during the interwar years. In World War II, Arnold served as chief of the U.S. Army Air Corps (1938-1941) and commanding general of the U.S. Army Air Forces (1942-1945). Arnold also played a major role in the development of civil aviation, co-founding Pan American Airways in 1927. A brilliant strategic thinker, in 1945 he founded Project RAND, which evolved into one of the world's largest and most influential global policy think tanks. (Section 34, Grave 44-A)

George Scratchley Brown (1918-1978) — A highly decorated World War II hero, General George Scratchley Brown was appointed chief of staff of the U.S. Air Force (August 1973-June 1974) and then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (from July 1974 until his retirement in 1978). During World War II, he flew B-24s with the 93rd Bombardment Group, earning the Distinguished Service Cross for his role in the low-level bombing of oil refineries in Ploesti, Romania in 1943. Brown held major air commands during the Korean War, and during the Vietnam War, as commander of the Seventh Air Force, effectively oversaw the United States' air operations in Southeast Asia. (Section 21, Grave S-24)

Claire L. Chennault (1893-1958) — General Claire Chennault earned his wings during World War I and went to China in 1937, shortly after the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War, to help train the Chinese Air Force. In 1940, he organized a group of volunteer American aviators, known as the "Flying Tigers," to assist the Chinese Air Force against the Japanese. The Flying Tigers were incorporated into the 14th Air Force after the United States entered the war. Chennault also played a leading role in developing civil air transport in China. (Section 2, Grave 873-3-4)

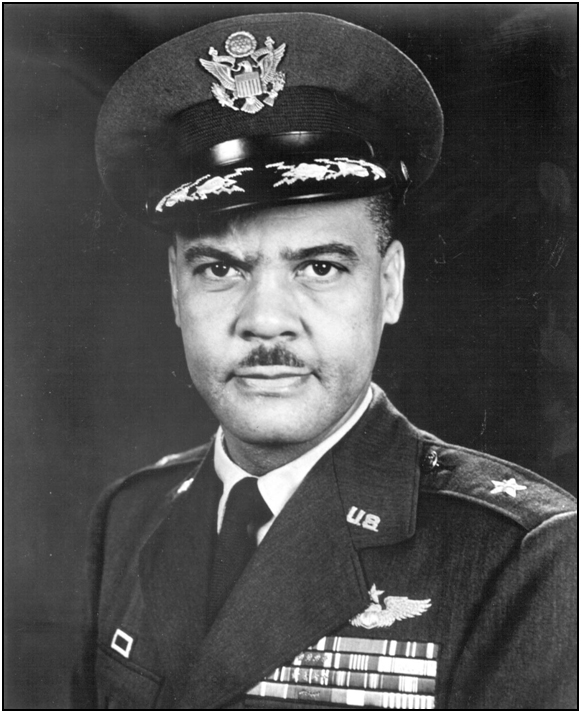

Benjamin O. Davis Jr. (1912-2002) — The son of Brig. Gen. Benjamin O. Davis Sr., Gen. Benjamin O. Davis Jr. was the first African American general in the U.S. Air Force. During World War II, he commanded the 99th Pursuit Squadron — the first all-Black American air unit, which flew tactical support missions in the Mediterranean theater — and the 332nd Fighter Group, more famously known as the Tuskegee Airmen. Davis commanded a fighter wing in the Korean War and subsequently held major peacetime command posts in Asia, Europe and the United States. He advanced to four-star rank in 1998. (Section 2, Grave E-311)

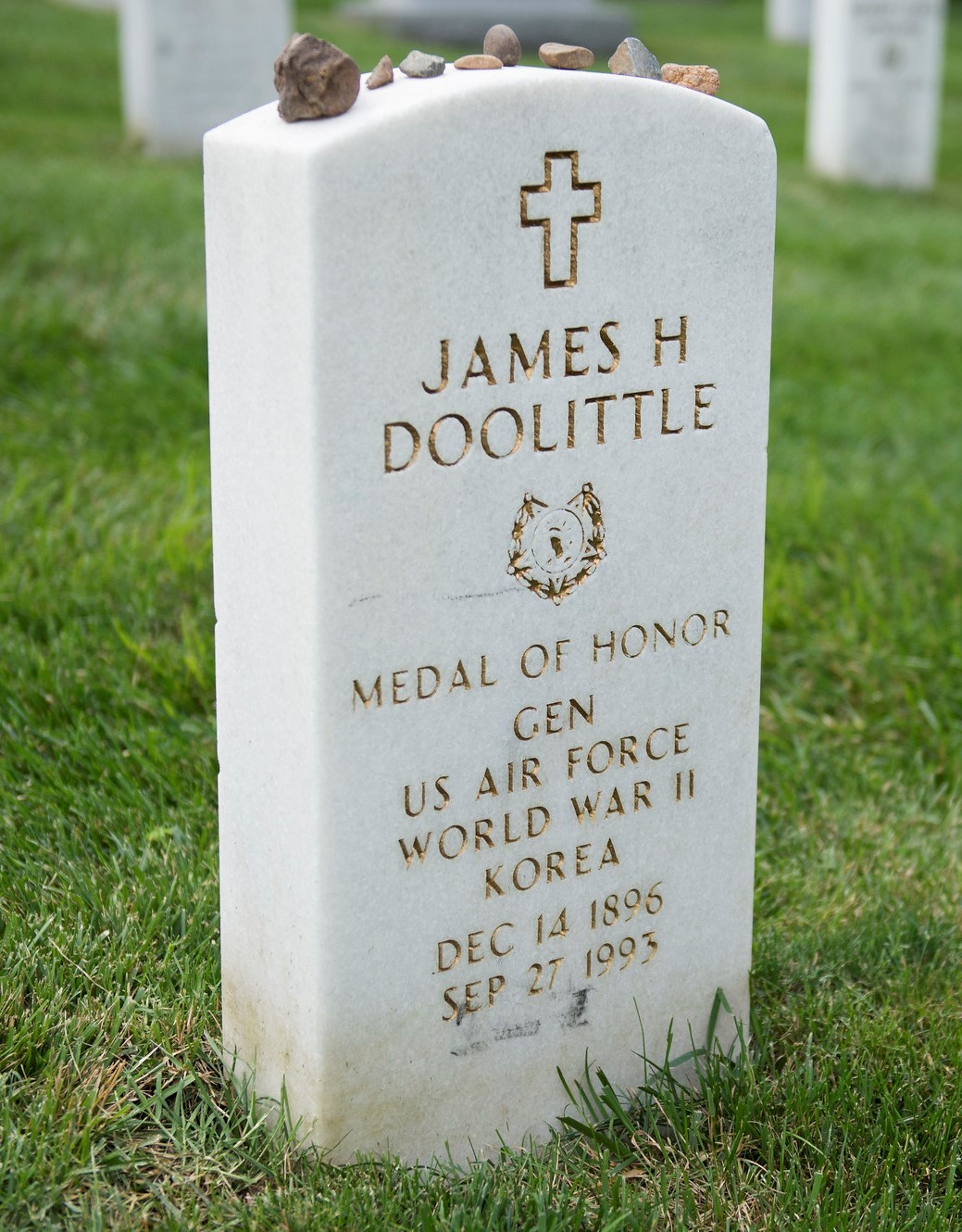

James H. "Jimmy" Doolittle (1896-1993) — The first Air Force general to wear four stars, Jimmy Doolittle was an aviation pioneer and famed World War II air commander. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for personal valor and leadership as commander of the Doolittle Raid, a bold long-range retaliatory air raid on the Japanese mainland, on April 18, 1942. Promoted to lieutenant general, he commanded the 12th Air Force over North Africa, the 15th Air Force over the Mediterranean and the 8th Air Force over Europe. Between the world wars, Doolittle was instrumental in the development of American aviation, setting numerous speed records and, in 1922, making the first cross-country flight (for which he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross). He continued these pioneering efforts after the war, advising the development of ballistic missiles and space programs as a special advisor to the Air Force chief of staff. Doolittle also helped organize and served as the first president of the Air Force Association. (Section 7A, Grave 110)

James H. "Jimmy" Doolittle (1896-1993) — The first Air Force general to wear four stars, Jimmy Doolittle was an aviation pioneer and famed World War II air commander. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for personal valor and leadership as commander of the Doolittle Raid, a bold long-range retaliatory air raid on the Japanese mainland, on April 18, 1942. Promoted to lieutenant general, he commanded the 12th Air Force over North Africa, the 15th Air Force over the Mediterranean and the 8th Air Force over Europe. Between the world wars, Doolittle was instrumental in the development of American aviation, setting numerous speed records and, in 1922, making the first cross-country flight (for which he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross). He continued these pioneering efforts after the war, advising the development of ballistic missiles and space programs as a special advisor to the Air Force chief of staff. Doolittle also helped organize and served as the first president of the Air Force Association. (Section 7A, Grave 110)

Claire Garrecht (1922-2000) — A decorated Air Force nurse, Claire Marie Garrecht became chief of the Air Force Nurse Corps in May 1974 and was promoted to brigadier general three months later. She began her career during World War II, receiving a commission in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps after earning degrees in nursing and education. She joined the Air Force in 1951 and subsequently served at numerous air bases in the United States and Britain. From 1965 to 1968, during the Vietnam War, she served as chief nurse of the 10th Aeromedical Evacuation Group at Hawaii’s Hickam Air Force Base, where she was responsible for the in-flight care of all patients transferred from Southeast Asia to the United States. Her awards included the Legion of Merit, the Meritorious Service Medal and the Air Medal. (Section 21, Grave 445)

Marcelite Jordan Harris (1943-2018) — Maj. Gen. Marcelite Jordan Harris retired in 1997 as the highest-ranking female officer in the Air Force and the highest ranking African American woman in the Department of Defense. A graduate of Spelman Academy, she was commissioned in 1965, rising through the ranks to become, in 1991, the first African American female brigadier general in the Air Force. Many of her assignments represented "firsts" for women in the Air Force. Her medals include the Bronze Star and the Legion of Merit. On February 7, 2019, she was laid to rest at Arlington with a military honors with escort funeral that included a flyover (pictured, above and at top of page). (Section 30, Grave 621)

Jeanne M. Holm (1921-2010) — The first woman to serve as a major general in the U.S. armed forces, Maj. Gen. Jeanne Holm had a long and distinguished career in the Air Force. She enlisted in the Army in 1942, soon after the establishment of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAC). She transferred to the Air Force in 1949 and was appointed director of Women in the Air Force (WAF) in 1965. During her tenure as director, policies affecting women were updated, WAF strength more than doubled and job and assignment opportunities greatly expanded. Her awards include the Distinguished Service Medal and the Legion of Merit. (Section 65, Grave 245)

Jeanne M. Holm (1921-2010) — The first woman to serve as a major general in the U.S. armed forces, Maj. Gen. Jeanne Holm had a long and distinguished career in the Air Force. She enlisted in the Army in 1942, soon after the establishment of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAC). She transferred to the Air Force in 1949 and was appointed director of Women in the Air Force (WAF) in 1965. During her tenure as director, policies affecting women were updated, WAF strength more than doubled and job and assignment opportunities greatly expanded. Her awards include the Distinguished Service Medal and the Legion of Merit. (Section 65, Grave 245)

James Jabara (1923-1966) — The son of Lebanese immigrants, James Jabara was the United States’ first jet ace. He enlisted as a cadet in the Army Air Corps after graduating from high school in 1942, determined to fly despite being short for a pilot (5’5”). During World War II, he flew P-51 Mustangs with the 363rd Fighter Group of the Ninth Air Force, completing 108 fighter-bomber missions over France and the Low Countries and earning the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal. In 1948, he made his first jet flight in a Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star jet fighter. During the Korean War, Jabara flew the F-86 Sabre, completing 163 missions in two tours of duty. With 15 confirmed victories, he was the second highest-ranking ace of the war, in addition to being the first U.S. jet ace; on May 20, 1951, he shot down his fifth and sixth MiGs within ten minutes. Back home, the Air Force sent Jabara on a publicity tour as the Korean War’s first American air hero, and he and his parents became local celebrities in their hometown of Wichita, Kansas. Jabara subsequently held commands at various air bases across the United States and was promoted to colonel in 1961. On November 17, 1966, he and his teenaged daughter, Carol Ann, were killed in an automobile accident in Florida. They are buried together at Arlington. (Section 2, Grave E-478-D)

James Jabara (1923-1966) — The son of Lebanese immigrants, James Jabara was the United States’ first jet ace. He enlisted as a cadet in the Army Air Corps after graduating from high school in 1942, determined to fly despite being short for a pilot (5’5”). During World War II, he flew P-51 Mustangs with the 363rd Fighter Group of the Ninth Air Force, completing 108 fighter-bomber missions over France and the Low Countries and earning the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal. In 1948, he made his first jet flight in a Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star jet fighter. During the Korean War, Jabara flew the F-86 Sabre, completing 163 missions in two tours of duty. With 15 confirmed victories, he was the second highest-ranking ace of the war, in addition to being the first U.S. jet ace; on May 20, 1951, he shot down his fifth and sixth MiGs within ten minutes. Back home, the Air Force sent Jabara on a publicity tour as the Korean War’s first American air hero, and he and his parents became local celebrities in their hometown of Wichita, Kansas. Jabara subsequently held commands at various air bases across the United States and was promoted to colonel in 1961. On November 17, 1966, he and his teenaged daughter, Carol Ann, were killed in an automobile accident in Florida. They are buried together at Arlington. (Section 2, Grave E-478-D)

Daniel "Chappie" James (1920-1978) — The first African American four-star officer in the armed forces, Gen. Daniel "Chappie" James Jr. was a decorated fighter pilot who earned his Army Air Corps wings in 1943 at Tuskegee Army Airfield, where he trained pilots for the all-Black 99th Pursuit Squadron during World War II. He flew 101 combat missions in Korea and 78 combat missions in Vietnam — including a flight in "Operation Bolo" on January 2, 1967, which destroyed seven Communist MiGs, the highest total kill of any mission during the Vietnam War. James was promoted to the four-star rank of general in 1975, and assigned as commander-in-chief of NORAD/ADCOM at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado. (Section 2, Grave 4968)

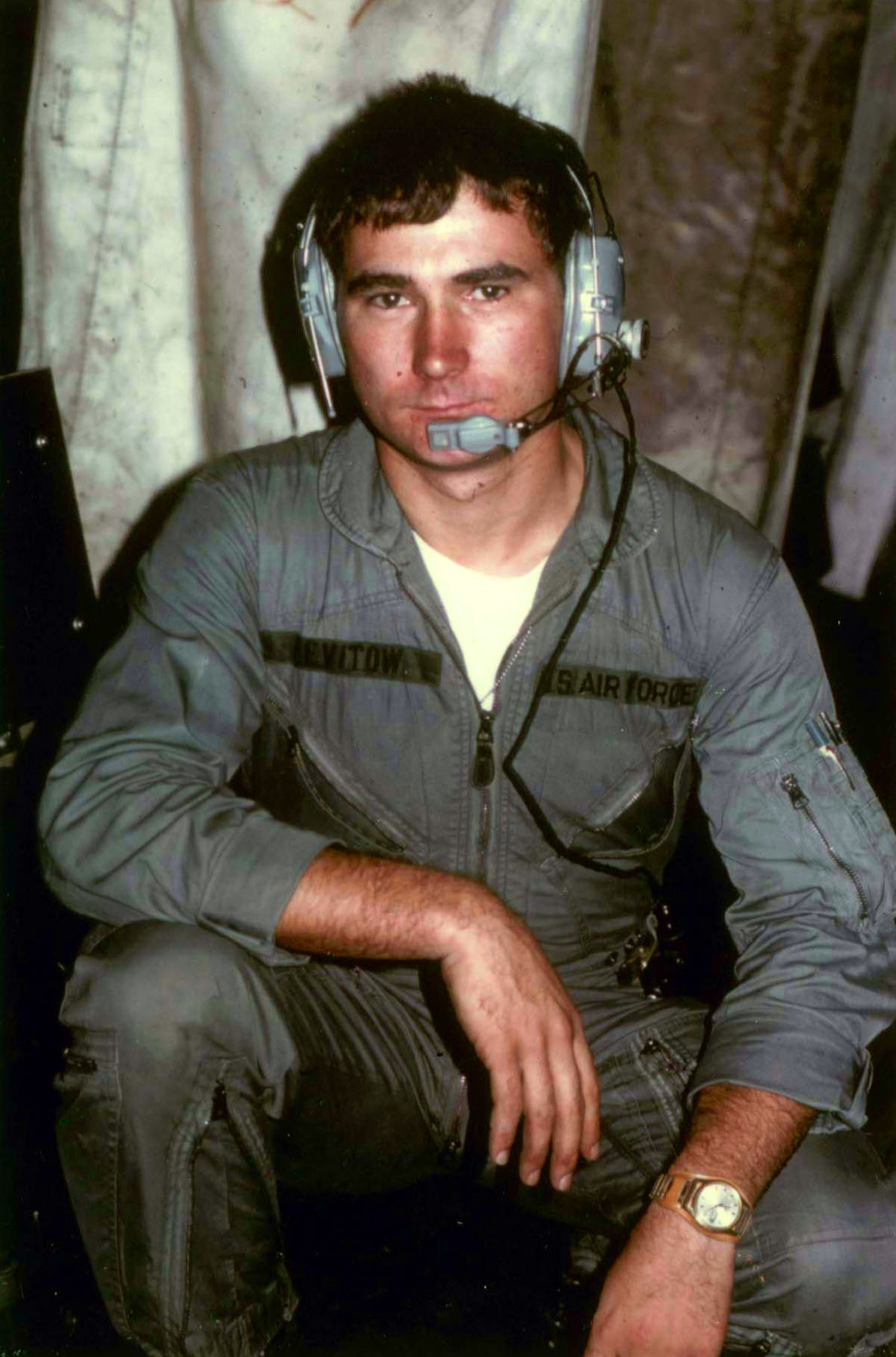

John Levitow (1945-2000) — John Lee Levitow, who served in Vietnam as a loadmaster aboard AC-47 “Spooky” gunships, is the lowest-ranking member of the Air Force to earn the Medal of Honor. On the night of February 24, 1969, Levitow’s plane was flying a mission in support of the Long Binh Army Post when it was struck by a mortar round. According to Levitow’s Medal of Honor citation, “Sgt. [Airman First Class at the time of action] Levitow, though stunned by the concussion of the blast and suffering from over 40 fragment wounds in the back and legs … struggled forward despite the loss of blood from his many wounds [and] threw himself bodily upon the burning flare. Hugging the deadly device to his body, he dragged himself back to the rear of the aircraft and hurled the flare through the open cargo door. At that instant the flare separated and ignited in the air, but clear of the aircraft. Sgt. Levitow, by his selfless and heroic actions, saved the aircraft and its entire crew from certain death and destruction.” After leaving the Air Force, Levitow spent more than 22 years working in veterans affairs in both Washington, D.C. and his home state of Connecticut. At the Air Force Memorial, his words are inscribed on the panel for Service: “I have been recognized as a hero for ten minutes of action over Vietnam, but I am no more a hero than anyone else who has served their country. (Section 66, Grave 7107)

John Levitow (1945-2000) — John Lee Levitow, who served in Vietnam as a loadmaster aboard AC-47 “Spooky” gunships, is the lowest-ranking member of the Air Force to earn the Medal of Honor. On the night of February 24, 1969, Levitow’s plane was flying a mission in support of the Long Binh Army Post when it was struck by a mortar round. According to Levitow’s Medal of Honor citation, “Sgt. [Airman First Class at the time of action] Levitow, though stunned by the concussion of the blast and suffering from over 40 fragment wounds in the back and legs … struggled forward despite the loss of blood from his many wounds [and] threw himself bodily upon the burning flare. Hugging the deadly device to his body, he dragged himself back to the rear of the aircraft and hurled the flare through the open cargo door. At that instant the flare separated and ignited in the air, but clear of the aircraft. Sgt. Levitow, by his selfless and heroic actions, saved the aircraft and its entire crew from certain death and destruction.” After leaving the Air Force, Levitow spent more than 22 years working in veterans affairs in both Washington, D.C. and his home state of Connecticut. At the Air Force Memorial, his words are inscribed on the panel for Service: “I have been recognized as a hero for ten minutes of action over Vietnam, but I am no more a hero than anyone else who has served their country. (Section 66, Grave 7107)

Geraldine Pratt May (1895-1997) — Geraldine Pratt May was the first director of Women in the Air Force (WAF), established in 1948 after the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act allowed women to enlist directly in the military during peacetime. As WAF director, May was promoted to colonel, becoming the first woman in the Air Force to hold that rank. She had previously served in the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) during World War II, and was selected for its first officers' training course. One of the first female officers assigned to the Army Air Forces, she served as WAC staff director of Air Transport Command. She received the Legion of Merit for her wartime service. May died in 1997 at the age of 102. (Columbarium Court 4, MM/16/1)

Noel F. Parrish (1907-1987) — Brig. Gen. Noel Parrish, a career military aviator, was best-known as the white commander of the Tuskegee Airmen (see below) — the military's first systematic effort to train African American pilots for combat duty during World War II. Under his leadership, 966 African American men completed military pilot training at Alabama's Tuskegee Army Airfield between 1941 and 1946. After the war, Parrish helped advise the Truman administration's desegregation of the armed forces, and he held several Air Force and NATO leadership positions. (Section 3, Grave 1667)

Elwood R. “Pete” Quesada(1904-1993) — Lt. Gen. Elwood Quesada's career spanned military and civil aviation. In 1929, as a reserve officer in the U.S. Army Air Corps, he served as a crew member on the record-setting "Question Mark" endurance flight, which stayed aloft for more than six days to demonstrate the feasibility of in-flight refueling. All five members of the crew, which also included legendary pilots Ira Eaker and Carl Spaatz, received the Distinguished Flying Cross. During World War II, Quesada held fighter commands during campaigns in Italy, North Africa and Europe, including the D-Day invasion in June 1944. He received two Distinguished Service Medals, the Legion of Merit and the Purple Heart. After retiring from active duty in 1951, Quesada entered private industry as an executive at Lockheed. From 1959 to 1961, he served as the first administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). (Section 30, Grave 439-LH)

Elwood R. “Pete” Quesada(1904-1993) — Lt. Gen. Elwood Quesada's career spanned military and civil aviation. In 1929, as a reserve officer in the U.S. Army Air Corps, he served as a crew member on the record-setting "Question Mark" endurance flight, which stayed aloft for more than six days to demonstrate the feasibility of in-flight refueling. All five members of the crew, which also included legendary pilots Ira Eaker and Carl Spaatz, received the Distinguished Flying Cross. During World War II, Quesada held fighter commands during campaigns in Italy, North Africa and Europe, including the D-Day invasion in June 1944. He received two Distinguished Service Medals, the Legion of Merit and the Purple Heart. After retiring from active duty in 1951, Quesada entered private industry as an executive at Lockheed. From 1959 to 1961, he served as the first administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). (Section 30, Grave 439-LH)

Francis Gary Powers (1929-1977) – Commissioned in 1952 after graduating from the United States Air Force Academy, Francis Gary Powers flew F-84s for the Air Force until January 1956, when he was recruited by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to participate in the top-secret U-2 aerial reconnaissance program. The U-2 “spy plane” flew at such high altitudes—up to 70,000 feet—that it was believed to be undetectable by ground radar. On May 1, 1960, however, Powers’ U-2 was shot down in Soviet airspace, over the city of Sverdlovsk, by a surface-to-air missile. The Soviets took Powers prisoner, convicted him of espionage and sentenced him to three years of imprisonment plus seven years of hard labor. On February 10, 1962, he was released in exchange for Colonel Rudolph Abel, a Soviet spy who had been held by the United States. (These events were dramatized in the 2015 Steven Spielberg movie “Bridge of Spies.”) Declassified documents indicate that he followed orders by refusing to reveal secret information or to denounce the United States. After his return to the U.S., Powers worked for Lockheed and flew helicopters for radio and television stations in Los Angeles. He was tragically killed in a helicopter crash on August 1, 1977, while working for KBNC News. In 2000, the U.S. military posthumously awarded Powell the Prisoner of War Medal. (At the time of Powers’ capture, he had not been recognized as a POW because the United States was not engaged in armed conflict with the Soviet Union, and he was believed to be working only for the CIA. In the late 1990s, however, declassified documents revealed that his mission had been a joint CIA-Air Force operation, thereby rendering him eligible for POW status.) Pictured: Powers, right, with U-2 designer Kellly Johnson in 1966. (Section 11, Grave 685-2)

James Robinson Risner (1925-2013) — Promoted to brigadier general upon his retirement from the Air Force in 1976, James Robinson "Robbie" Risner was a decorated fighter ace in the Korean and Vietnam Wars. In Korea, he shot down eight MiGs; in Vietnam, he led the first flights of Operation Rolling Thunder, the United States’ 1965 intensive bombing campaign against North Vietnam. He received the Air Force Cross in April 1965, and was featured on the cover of Time magazine. On September 16, 1965, however, Risner was shot down and captured. He subsequently survived more than seven years as a prisoner of war (POW) at the infamous “Hanoi Hilton” prison in North Vietnam. Due to the Time cover story, the North Vietnamese believed him to be of special importance. Guards singled him out for additional torture and abuse—including long stints in solitary confinement that totaled more than three years. Still, Risner’s remarkable resilience helped his fellow POWs to endure their own experiences. In 1971, Risner organized a church service, a forbidden activity. As guards led him away to solitary confinement, more than 40 other POWs broke out singing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” At that moment, he recalled, “I felt like I was nine feet tall and could go bear hunting with a switch.” In 2001, the Air Force Academy installed a nine-foot-tall statue of General Risner to honor his heroism. (Section 55, Grave 626)

James Robinson Risner (1925-2013) — Promoted to brigadier general upon his retirement from the Air Force in 1976, James Robinson "Robbie" Risner was a decorated fighter ace in the Korean and Vietnam Wars. In Korea, he shot down eight MiGs; in Vietnam, he led the first flights of Operation Rolling Thunder, the United States’ 1965 intensive bombing campaign against North Vietnam. He received the Air Force Cross in April 1965, and was featured on the cover of Time magazine. On September 16, 1965, however, Risner was shot down and captured. He subsequently survived more than seven years as a prisoner of war (POW) at the infamous “Hanoi Hilton” prison in North Vietnam. Due to the Time cover story, the North Vietnamese believed him to be of special importance. Guards singled him out for additional torture and abuse—including long stints in solitary confinement that totaled more than three years. Still, Risner’s remarkable resilience helped his fellow POWs to endure their own experiences. In 1971, Risner organized a church service, a forbidden activity. As guards led him away to solitary confinement, more than 40 other POWs broke out singing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” At that moment, he recalled, “I felt like I was nine feet tall and could go bear hunting with a switch.” In 2001, the Air Force Academy installed a nine-foot-tall statue of General Risner to honor his heroism. (Section 55, Grave 626)

Hector Santa Anna (1923-2006) — After enlisting in the Army in 1943, Hector Santa Anna completed his flight training at Brooks Army Air Field in San Antonio, Texas—ironically, near where his great-great uncle, the Mexican General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, had laid siege to the Alamo over a century before. Among the 97 cadets in his class, Santa Anna was the only Latino. The Army utilized Santa Anna’s bilingualism by assigning him to train Central and South American military pilots at Waco Army Air Field in Texas. He volunteered for combat duty in August 1944, arriving in England that fall with the 486th Bomb Group, 3rd Bomb Wing, of the 8th Air Force. Between November 16, 1944 and March 3, 1945, Santa Anna flew 35 combat missions over western Europe, earning two Distinguished Service Medals, five Air Medals and a Commendation Medal. After the war, Santa Anna continued his military career in the nascent U.S. Air Force. During the Berlin Airlift (1948-1949), he flew 127 missions in support of Allied efforts to provide humanitarian aid to Soviet-blockaded Berlin. His later Air Force career took him to the Pentagon, where he served as special assistant to the secretary of defense for public affairs. He retired from the Air Force in June 1964 and subsequently held civilian leadership positions at NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). During the Nixon administration , he was the Office of Equal Opportunity’s White House representative and a member of the president’s Cabinet Committee on Opportunities for Spanish-Speaking People. (Section 54, Grave 571)

Bernard Schriever (1910-2005) — General Bernard Schriever (pictured, above) is known as the “father of the Air Force’s ballistic missile and space programs,” as his headstone states. Commissioned as an Army artillery officer, Schriever transferred to the Army Air Corps in 1937 and, during World War II, he flew bombing campaigns in the Pacific and commanded the Far East Air Service Command. After the war, his work focused on developing new jet and rocket technologies. In 1954, Schriever was assigned to command the Air Research and Development Command’s (ARDC’s) Western Development Division. He oversaw the development of the Thor, Atlas, Titan, and Minuteman missile systems—key pieces of the United States’ Cold War strategy of nuclear deterrence. He also directed Air Force support of NASA’s Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs. In 1961, Schriever became commander of the Air Force Systems Command and was promoted to four-star general. After retiring from the Air Force in 1966, he continued to advise the government and private industry on matters related to space, technology and management. He is the namesake of Schriever Air Force Base in Colorado, renamed in 1998 as the first base to be named after a living individual. (Section 34, Grave 162)

Nathan Farragut Twining (1897-1982) — In 1957, Twining became the first Air Force general to be appointed chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. As chief of staff of the Air Force (1953-1957) and as chairman of the Joint Chiefs (1957-1960), he implemented President Dwight D. Eisenhower's doctrine of "massive retaliation" — a Cold War strategy based on air power and nuclear strike capability. A career officer, he grew up in a Navy family (his middle name honored U.S. Navy Admiral David Farragut) and attended West Point only after failing the Naval Academy entrance examination. During World War II, he commanded the 20th Air Force in the Pacific, which carried out the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan in August 1945. (Section 30, Grave 434-2)

USAF Astronauts at ANC

The Challenger (left) and Columbia (right) Memorials in Section 46.

Charles A. Bassett II (1931-1966) — A member of NASA's Group 3 Astronaut Class, Maj. Charles A. Bassett II was scheduled to fly Gemini 9 in the spring of 1966. On February 28, 1966, Bassett and Gemini 9 command pilot Elliot See died when their T-38 supersonic training jet crashed at Lambert Field in St. Louis, Missouri. Bassett and See are buried near each other. (Section 4, Grave 195)

Donn F. Eisele (1930-1987) — Col. Donn Eisele served as command module pilot for Apollo 7, the first crewed mission of the Apollo program, from October 11 to 22, 1968. In his post-NASA career, Eisele directed the Peace Corps in Thailand for two years. (Section 3, Grave 2503-G-1)

Theodore C. Freeman (1930-1964) — A USAF test pilot and aeronautical engineer, Capt. Theodore Freeman was selected to become an astronaut in 1963, as part of NASA's third "class." On the morning of October 31, 1964, he was piloting a T-38 supersonic jet trainer that crashed while returning to Ellington Air Base. Freeman was the first American to lose his life in the space program. (Section 4, Grave 3148-LH)

Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom (1926-1967) — Lt. Col. Virgil Ivan "Gus" Grissom was killed on January 27, 1967, along with fellow astronauts Lt. Cmdr. Roger B. Chaffee and Lt. Col. Ed White, in a fire aboard the Apollo 1 spacecraft during a launch rehearsal at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Selected as one of the original "Mercury Seven," Grissom was an accomplished fighter pilot who had flown 100 missions during the Korean War and subsequently tested fighter jets for the Air Force. On July 21, 1961, he became the second NASA astronaut in space (after Alan Bartlett Shepard Jr.). When he piloted Gemini 3 on March 23, 1965, he became the first American to venture into space twice. He was assigned to command the first crewed Apollo mission. Grissom is buried next to Roger Chaffee. (Section 3, Grave 2503-E)

James Benson Irwin (1930-1991) — Col. James Irwin piloted the lunar module for the Apollo 15 mission (July 26-August 7, 1971) and spent nearly three days on the moon's surface. He later founded a Christian evangelical organization, the High Flight Foundation, and credited his experiences in space with his spiritual reawakening. (Section 3, Grave 2503-G-2)

Stuart A. Roosa (1933-1994) — Before joining the Air Force, Stuart Roosa worked as a smoke jumper for the U.S. Forest Service, parachuting into remote locations to put out wildfires. He was the command module pilot for Apollo 14 (January 31 to February 9, 1971), the third lunar landing mission. At the request of the Forest Service director, Col. Roosa carried hundreds of seeds with him on that mission, which were later planted to become "moon trees" throughout the United States. (Section 7A, Grave 73)

Space Shuttle Challenger Memorial — On January 28, 1986, the space shuttle Challenger exploded just 73 seconds after takeoff, killing all seven crew members. A memorial, dedicated in May 1986, marks a gravesite containing the crew members' comingled remains (Section 46, Grave 1129). The Challenger's crew included two active-duty Air Force officers: mission commander Maj. Francis R. "Dick" Scobee (retired with honorary promotion to Lt. Col.) and Capt. Ellison Onizuka, the first person of Japanese ancestry to travel to space. Scobee's individual gravesite is to the left of the memorial. (Section 46)

Space Shuttle Columbia Memorial — On February 1, 2003, the space shuttle Columbia was headed home after a 16-day scientific mission, its 28th venture into space. As Columbia re-entered Earth's atmosphere, it suddenly burst into flames, killing all seven crew members. The crew included two members of the U.S. Air Force, Lt. Col. Michael P. Anderson and Col. Rick D. Husband. Commingled remains of all seven Columbia astronauts are interred below a memorial in Section 46, Grave 1180. Those who could be identified individually, including Anderson, also have individual gravesites nearby. (Section 46)

Pre-USAF Aviation Notable Graves

Floyd Bennett, U.S. Navy (1890-1928) — According to their own accounts, pioneering naval aviator Floyd Bennett and Adm. Richard E. Byrd accomplished the first flight over the North Pole on May 9, 1926. Piloting a Fokker Tri-motor, Bennett took off from the Norwegian Arctic island of Spitsbergen, crossed the pole and returned 16 hours later. Although some have contended that Bennett and Byrd did not make it all the way to the North Pole, the flight — 1,545 miles amid extremely strong winds — was nonetheless a significant accomplishment. Along with Byrd, Bennett received the Medal of Honor for the flight, and he became the namesake of New York's first municipal airport, Floyd Bennett Field. (Section 3, Grave 1852-B)

Gregory "Pappy" Boyington, U.S. Marine Corps (1912-1988) — A World War II fighter ace and Medal of Honor recipient, Col. "Pappy" Boyington shot down a total of 28 Japanese aircraft. Initially in Army ROTC, he joined the Marines in 1935. In August 1941, however, he resigned his Marine commission in order to join the Flying Tigers (1st American Volunteer Group), organized by Gen. Claire Chennault to assist the Chinese Air Force. Boyington rejoined the Marines in 1942 and commanded the "Black Sheep" squadron (Marine Fighting Squadron 214) in the South Pacific. On January 3, 1944, he was shot down, captured and then held in a Japanese prison camp for 20 months. Boyington's 1958 memoir, "Baa Baa Black Sheep," inspired the 1970s television series of the same name. (Section 7A, Grave 150)

Gregory "Pappy" Boyington, U.S. Marine Corps (1912-1988) — A World War II fighter ace and Medal of Honor recipient, Col. "Pappy" Boyington shot down a total of 28 Japanese aircraft. Initially in Army ROTC, he joined the Marines in 1935. In August 1941, however, he resigned his Marine commission in order to join the Flying Tigers (1st American Volunteer Group), organized by Gen. Claire Chennault to assist the Chinese Air Force. Boyington rejoined the Marines in 1942 and commanded the "Black Sheep" squadron (Marine Fighting Squadron 214) in the South Pacific. On January 3, 1944, he was shot down, captured and then held in a Japanese prison camp for 20 months. Boyington's 1958 memoir, "Baa Baa Black Sheep," inspired the 1970s television series of the same name. (Section 7A, Grave 150)

Richard Byrd, U.S. Navy (1888-1957) — An Arctic explorer and naval aviator, Rear Admiral Richard Byrd was the first person to fly over both poles of the Earth, reaching the North Pole in 1926 and the South Pole in 1929. He and pilot Floyd Bennett (Section 3, Grave 1852) each received a Medal of Honor for their North Pole flight. Congress promoted Byrd to rear admiral (retired) after his South Pole expedition. Byrd continued exploring Antarctica throughout his life; he was 67 years old at the time of his last expedition, in 1955. (Section 2, Grave 4969)

Juanita Redmond Hipps, U.S. Army (1912-1979) — During World War II, Juanita Redmond (later Juanita Redmond Hipps; pictured at left) helped to establish the Army Air Corps flight nurse program and was among the first nurses to earn gold flight wings. The Air Force Association created the Juanita Redmond Award, its highest honor in the nursing field, in recognition of her distinguished service. Reaching the rank of lieutenant colonel, Redmond Hipps also served as an Army nurse in the Philippines during World War II. Her bestselling 1943 memoir, "I Served on Bataan,” inspired the movie “So Proudly We Hail,” also released in 1943. (Section 21, Grave 769-1)

Frank S. Scott, U.S. Army (1883-1912) — In a tragic milestone of aviation history, Cpl. Frank Scott was American military aviation's first enlisted casualty. Scott had trained as an airplane mechanic at the Army Signal Corps' Aviation School at College Park Flying Field, Maryland. On September 28, 1912, he was the passenger of a student pilot at the school. Their Wright Model B airplane developed engine trouble and crashed, killing both aboard. Cpl. Scott is the namesake of Illinois' Scott Air Force Base. (Section 13, Grave 5331-S)

Thomas Selfridge, U.S. Army (1882-1908) — The first person to die in the crash of a powered airplane, during a demonstration flight with Orville Wright on September 17, 1908, First Lt. Thomas Selfridge made key contributions to the development of aviation. He designed the first powered aircraft for the Aerial Experiment Association (an important research group chaired by Dr. Alexander Graham Bell) and, shortly before his death, made the first dirigible flights for the Army Signal Corps. (Section 3, Grave 2158)

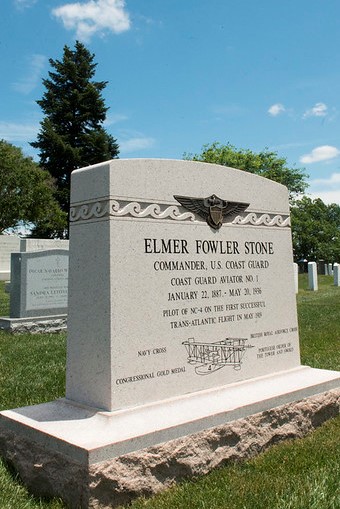

Elmer Fowler Stone, U.S. Coast Guard (1887-1936) — The U.S. Coast Guard's first aviator, Stone flew seaplanes for the U.S. Navy during World War I and advocated for the development of Coast Guard aviation. In May 1919, he piloted the first successful flight across the Atlantic Ocean, a 54-hour feat via Nova Scotia and the Azores. (Eight years later, Charles Lindbergh would accomplish the first non-stop transatlantic flight.) During the 1920s and 1930s, Cmdr. Stone tested new types of seaplanes for the Coast Guard and Navy, and in 1934 he set a world speed record for amphibian aircraft. (Section 4, 3205-A)

Elmer Fowler Stone, U.S. Coast Guard (1887-1936) — The U.S. Coast Guard's first aviator, Stone flew seaplanes for the U.S. Navy during World War I and advocated for the development of Coast Guard aviation. In May 1919, he piloted the first successful flight across the Atlantic Ocean, a 54-hour feat via Nova Scotia and the Azores. (Eight years later, Charles Lindbergh would accomplish the first non-stop transatlantic flight.) During the 1920s and 1930s, Cmdr. Stone tested new types of seaplanes for the Coast Guard and Navy, and in 1934 he set a world speed record for amphibian aircraft. (Section 4, 3205-A)

Tuskegee Airmen — In spite of the accomplishments of numerous Black civilian aviators during the early 20th century, prior to World War II the U.S. military did not permit African Americans to become aviators. However, in response to a pilot shortage in the United States as well as pressure from civil rights groups, in June 1941 the U.S. Army Air Corps launched an experimental training program for African American aviators, located at Tuskegee Army Airfield near Tuskegee Institute, a historically Black university in Alabama. Between 1941 and 1946, 966 African American men completed military pilot training at Tuskegee. Comprising the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Composite Group of the U.S. Army Air Forces, the "Tuskegee Airmen" completed more than 1,800 missions during World War II. A memorial tree and plaque stand in Section 46 of the cemetery.

► See also:

Image Sources (top to bottom):