United States Navy

The United States Navy traces its origins to the Continental Navy, established during the Revolutionary War. On October 13, 1775, the Continental Congress created the Continental Navy, then comprised of only two armed ships, to sail along the Atlantic coast in search of British munitions ships. After the war, the Constitution of the United States, ratified in 1789, empowered the newly-established Congress “to provide and maintain a navy.” The War Department administered naval affairs until April 30, 1798, when Congress established the Department of the Navy. In 1972, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Elmo R. Zumwalt authorized official recognition of October 13 as the birthday of the United States Navy.

To commemorate the Navy’s 245th birthday, read our blog posts, "The Navy Legacy at Arlington National Cemetery" and "'The Monitor Is No More': Honoring the Lost Men of USS Monitor," and scroll down to learn more about Navy gravesites and memorials at Arlington. Here, we highlight selected individuals who have made key contributions to U.S. Navy history. Every day, however, we honor all sailors buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Each Navy gravesite represents service and sacrifice that contributed to victory at sea.

Notable Navy Graves at Arlington National Cemetery

Richard Halsey Best (1910-2001) — A U.S. Naval Academy graduate and decorated World War II naval aviator, Lt. Richard Halsey Best earned the Navy Cross and the Distinguished Flying Cross for his courageous actions in the Battle of Midway, which paved the way for a U.S. victory in the Pacific Theater. In 1940, as the U.S. military began to mobilize in preparation for possible war, Best was assigned to a bombing squadron on the USS Enterprise, and in early 1942 he took part in bombing raids against the Japanese-occupied Marshall Islands. On June 4, 1942, Best commanded Bombing Squadron 6 (VB-6) and led successful attacks against two Japanese aircraft carriers, the Akagi and the Hiryu. According to some eyewitness accounts, Best’s own plane delivered the bombs that fatally damaged the Akagi and the Hiryu. By halting the advance of Japanese forces at Midway, the U.S. assumed an offensive position for the remainder of the war, leading to its eventual victory. (Section 54, Grave 3192)

Winifred Quick Collins (1911-1999) — In June 1942, Winifred Quick Collins, a graduate of Radcliffe College’s Business Administration Program, was commissioned as an ensign in the Navy WAVES (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service). She was soon deployed to Washington, D.C. to help operate the Bureau of Naval Personnel, where her responsibilities included determining what skills women in the WAVES would need to acquire during training. In the fall of 1944, Collins was named district personnel manager for the 14th Naval District in Hawaii, where she organized the arrival of 5,000 WAVES. She received the Bronze Star for her service during World War II. After the war, she oversaw the enlistment of women into the regular Navy and became a commissioned Navy officer (along with eight other women) in June 1948. Promoted to commander in 1953, she served as personnel director for the 12th Naval District—at the time, the highest position held by a woman in the Navy. She is pictured here with President John F. Kennedy in July 1962; she retired from the Navy later that year at the rank of captain. In 1990, Captain Collins became the first woman named to the Navy League’s Hall of Fame. She is buried with her husband, Rear Admiral Howard Lyman Collins, who served on the staff of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz during World War II. (Section 3, Grave 1632-C)

John "Jackie" Cooper Jr. (1922-2011) — Jackie Cooper was a child star who became the youngest Oscar nominee for his role in the film "Skippy" (1931). As "America's Boy" reached adulthood, his acting career stalled, and so Cooper enlisted in the Navy during World War II. He received the Legion of Merit for his service in the South Pacific. After the war, he played a Navy doctor in the television series "Hennesey" (1959-1962) and appeared in many other film and TV productions, including the "Superman" movies. Cooper remained active in the Naval Reserve, working in recruitment and public affairs, and ultimately attained the rank of captain. (Section 64, Grave 1903)

John Follin (1761-1841) — John Follin, from Virginia, is the only Continental Navy sailor buried at Arlington. During the Revolutionary War, Follin joined the Continental Navy as a teenager; he was just 17 years old when British sailors took him captive as a prisoner of war. Follin was held as a POW for three years. After his death in 1841, he was originally buried in Falls Church, Virginia, but his family later requested that his remains be moved to Arlington. His reinterment took place on May 13, 1911. Follin is one of eleven Revolutionary War veterans who were reinterred at Arlington between 1892 and 1943. (Section 1, Grave 295-1-2)

James V. Forrestal (1892-1949) — The United States' first secretary of defense, Forrestal served in that position from 1947 to 1949 — following the National Security Act of 1947, which unified the U.S. armed forces under the newly-created Department of Defense. In addition to guiding the military through this bureaucratic reorganization, Forrestal helped to formulate early Cold War defense policy. The former investment banker had proven himself to be a skilled military administrator during World War II: as undersecretary and then secretary of the Navy, he organized the Navy's massive wartime expansion and procurement programs. The inscription on his headstone reads: "In the great cause of good government." (Section 30, Grave 674)

John Brown Frazier (1870-1939) — During World War I, Chaplain John Brown Frazier created the foundations of the Navy’s modern chaplain system. His own Navy service began in 1895, when he was appointed as a chaplain to the U.S. Asiatic Squadron. Stationed in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War (1898), he reportedly stood beside Admiral George Dewey aboard the USS Olympia during the famed Battle of Manila Bay. After the United States entered World War I in 1917, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels appointed Frazier as the Navy’s first chief of chaplains. By the end of the war, Frazier had increased the number of active-duty Navy chaplains from 40 to almost 200; meanwhile, he instilled in the corps a distinct identity and ethos. He also authored “The Navy Chaplain’s Manual,” a standard-setting text first published in 1917. In 1921, Frazier was selected as one of four chaplains to participate in the state funeral of the Unknown Soldier of World War I, held at Arlington National Cemetery’s Memorial Amphitheater. He retired from the Navy in 1925. (Section 7, Grave 10058)

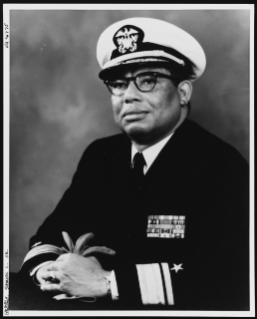

Samuel Lee Gravely Jr. (1922-2004) — The first African American Navy officer to rise to the rank of vice admiral, the first to command a warship and the first to command a U.S. fleet, Vice Admiral Samuel Lee Gravely Jr. served in the Navy for nearly 40 years, from 1942 to 1980. During World War II, he was the only African American officer on the USS PC-1264, a submarine chaser with a predominately Black crew. During the Vietnam War, when he took command of the destroyer escort USS Falgout, he became the first African American officer to command a combat ship. From 1976 to 1978, he commanded the Hawaii-based Third Fleet, and then directed the Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) until his retirement. (Section 66, Grave 7417)

Samuel Lee Gravely Jr. (1922-2004) — The first African American Navy officer to rise to the rank of vice admiral, the first to command a warship and the first to command a U.S. fleet, Vice Admiral Samuel Lee Gravely Jr. served in the Navy for nearly 40 years, from 1942 to 1980. During World War II, he was the only African American officer on the USS PC-1264, a submarine chaser with a predominately Black crew. During the Vietnam War, when he took command of the destroyer escort USS Falgout, he became the first African American officer to command a combat ship. From 1976 to 1978, he commanded the Hawaii-based Third Fleet, and then directed the Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) until his retirement. (Section 66, Grave 7417)

William Halsey Jr. (1882-1959) — Admiral William "Bull" Halsey, one of the most important naval commanders of World War II, was promoted to fleet admiral (five-star) in December 1945. A Naval Academy graduate and decorated veteran of World War I, he was a leading proponent of carrier-based air and naval warfare. During World War II, Halsey commanded U.S. Navy forces in the South Pacific in 1942-1943, and in 1944 he assumed command of the Third Fleet — which played a decisive role in the defeat of Japan. Adm. Halsey's flagship, the USS Enterprise, was the first carrier to be honored with the Presidential Unit Citation. Halsey's many individual awards included the Navy Cross, the Distinguished Service Medal with three Gold Stars and the Army Distinguished Service Medal. (Section 2, Grave 1184)

Joy Bright Hancock (1898-1986) — Captain Joy Bright Hancock’s service was instrumental to expanding women’s opportunities in the military. During World War I, Hancock enlisted in the Navy as a yeoman (F) first class; she served as a courier at the U.S. Naval Air Station in Cape May, New Jersey. She left the military when the war ended, but worked as a civilian for the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics. During World War II, after President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized creation of the Navy Women’s Reserve, or WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service), in 1942, Hancock was commissioned as a lieutenant and served as a liaison between the Bureau of Aeronautics and the WAVES. She became director of the WAVES in 1946. Hancock also played an important role in getting Congress to pass the Women Armed Services Integration Act of 1948, which secured women a permanent place in the military during peacetime. That year, she became one of the first six women sworn into the regular Navy. In 1972, Captain Hancock published her autobiography, “Lady in the Navy,” recounting her own experiences as well as the history of women in the Navy. She is buried with her husband, U.S. Navy Vice Admiral Ralph A. Ofstie. (Section 30, Grave 2138-RH)

Lenah S. Higbee (1874-1941) — Higbee completed nurse's training in 1899 in New York City and postgraduate studies at Fordham Hospital in 1908. Later that year, she joined the U.S. Navy, becoming one of its first 20 nurses. She became the Navy's chief nurse in 1909 and the second superintendent of the Navy Nurse Corps in 1911, a position she held through World War I. Higbee received the Navy Cross for distinguished service in 1918. (Section 3, Grave 1797)

Grace Hopper (1906-1992) — Rear Admiral Grace Hopper was a mathematician and a pioneer in computer science. At a time when few women pursued science or engineering degrees, Hopper earned her Ph.D. in mathematics from Yale University in 1934. She was a professor of mathematics at Vassar College (her undergraduate alma mater) until 1943, when she joined the U.S. Naval Reserve as a lieutenant. Assigned to the Bureau of Ships Computation Project at Harvard University, Hopper worked on Mark I, the first large-scale automatic calculator and a precursor of the computer. After the war, she remained at the Harvard Computation Lab for four years as a research fellow. In 1949, she joined the Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation, where she helped to develop the UNIVAC I, the first general-purpose electronic computer. Throughout her postwar career in academia and private industry, Hopper retained her naval commission. From 1967 to 1977, she directed the Navy Programming Languages Group in the Navy's Office of Information System Planning. When Rear Adm. Hopper retired from the Navy in 1986 at the age of 79, she was the oldest officer on active U.S. naval duty. (Section 59, Grave 973)

Grace Hopper (1906-1992) — Rear Admiral Grace Hopper was a mathematician and a pioneer in computer science. At a time when few women pursued science or engineering degrees, Hopper earned her Ph.D. in mathematics from Yale University in 1934. She was a professor of mathematics at Vassar College (her undergraduate alma mater) until 1943, when she joined the U.S. Naval Reserve as a lieutenant. Assigned to the Bureau of Ships Computation Project at Harvard University, Hopper worked on Mark I, the first large-scale automatic calculator and a precursor of the computer. After the war, she remained at the Harvard Computation Lab for four years as a research fellow. In 1949, she joined the Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation, where she helped to develop the UNIVAC I, the first general-purpose electronic computer. Throughout her postwar career in academia and private industry, Hopper retained her naval commission. From 1967 to 1977, she directed the Navy Programming Languages Group in the Navy's Office of Information System Planning. When Rear Adm. Hopper retired from the Navy in 1986 at the age of 79, she was the oldest officer on active U.S. naval duty. (Section 59, Grave 973)

Kara Spears Hultgreen (1965-1994) — Lt. Kara Spears Hultgreen was the first female carrier-based fighter pilot in the U.S. Navy, and the first woman to qualify as an F-14 combat pilot. She died on October 25, 1994 when her F-14 Tomcat crashed into the Pacific Ocean while making a final approach to the carrier USS Abraham Lincoln. (Section 60, Grave 7710)

Edouard Izac (1891-1990) — During World War I, Izac received the Medal of Honor for his daring efforts to escape German imprisonment in order to provide intelligence information to the Allies. After his ship, the USS President Lincoln, was attacked and sunk by German submarine U-90 in May 1918, Izac was held aboard the U-boat as a prisoner of war. Izac could understand German — his father had emigrated to the United States from Germany — and, as he overheard U-90 officers talking, he gathered information about the movements of German submarines. Determined to pass this information to his superiors, he attempted to escape twice, succeeding the second time. Izac also served as a member of Congress from 1937 to 1947, and he lived to be 100 years old. (Section 3, Grave 4222-16)

William Leahy (1875-1959) — Leahy was one of two admirals promoted to fleet admiral (five-star) in December 1944. He served in the Spanish-American War and World War I, and as chief of naval operations from 1937 to 1939, he oversaw the Navy's return to preparedness during the lead-up to World War II. He also served as governor of Puerto Rico, U.S. ambassador to France and chief of staff to Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman. (Section 2, Grave 932)

John McCloy (1876-1945) — A double Medal of Honor recipient, McCloy joined the U.S. Merchant Marine at age 15 and enlisted in the Navy in 1898, serving in the Spanish-American War. He received his first Medal of Honor for meritorious conduct during the China Relief Expedition of June 1900, and he received his second for leading three picket launches against heavy enemy fire during the U.S. occupation of Vera Cruz, Mexico in April 1914. For commanding a minesweeper that cleared the North Sea after World War I, he was awarded the Navy Cross. (Section 8, Grave 5246)

Arthur W. Radford (1896-1973) — Admiral Arthur Radford was chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1953 to 1957. He had previously served as commander-in-chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet during the Korean War, and as an aircraft carrier division commander in the Pacific during World War II. A naval aviator, Radford advocated naval air power and the strong anti-communist deterrence policies of President Dwight D. Eisenhower. (Section 30, Grave 435)

Barbara Allen Rainey (1948-1982) — The first woman pilot in the Navy, Lt. Cmdr. Rainey was commissioned in 1970 and accepted into flight training school in 1974. She resigned her commission in November 1977, while pregnant with her first daughter, but remained active in the Naval Reserves. She was recalled to duty as a flight instructor in 1981. On July 13, 1982, she was killed in an aircraft accident while training another pilot. (Section 6, Grave 5813-A-7)

Hyman G. Rickover (1900-1986) — The "Father of the Nuclear Navy," Rickover led the Navy's Naval Reactors division from 1949 to 1982, overseeing development of the nation's first nuclear submarines. Born in Poland, then part of the Russian Empire, Rickover's family emigrated to the United States when he was a child, as Jewish refugees from Russian pogroms. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy and served 63 years of active duty. Rickover is one of only four people to have received two Congressional Gold Medals for exceptional public service. (Section 5, Grave 7000)

William T. Sampson (1840-1902) — As commander of the North Atlantic Squadron during the Spanish-American War (1898), Sampson implemented the naval strategy that enabled the United States to achieve victory over Spain. However, he was absent (away conferring with the commander of U.S. land forces) during the decisive Battle of Santiago de Cuba, in which the Navy destroyed the Spanish fleet. This prompted a controversy over whether Sampson or Adm. Winfield S. Schley (buried in Section 2), who was in command during that battle, should receive credit for the victory. Sampson also served as president of the U.S.S. Maine court of inquiry, which investigated the explosion of the Maine in Havana Harbor. (Section 21, Grave S-9)

Henry Gabriel Sanchez (1907-1978) — Rear Admiral Henry Gabriel Sanchez, a U.S. Naval Academy graduate, was a decorated naval aviator. During World War II, he commanded Fighting Squadron 72 (VF-72), an F4F squadron of 37 aircraft, aboard the carrier USS Hornet. He received the Distinguished Flying Cross for meritorious achievement on October 26, 1942, during the Battle of Santa Cruz — the fourth major naval engagement between the United States and Japan. According to the medal citation, Sanchez "led a division of fighters in a determined and daring attack on Japanese interceptor planes." His other awards include the Air Medal with Gold Star and the Presidential Unit Citation with three stars. (Section 2, Grave 4736-3-4)

Navy Explorers of Earth and Space

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the United States Navy played a leading role in the geographical exploration of remote areas of the earth. This legacy continued with space exploration, as many U.S. astronauts served in the Navy and initially distinguished themselves as naval aviators. Prominent Navy explorers of earth and space buried at Arlington include:

Floyd Bennett (1890-1928) — According to their own accounts, pioneering naval aviators Floyd Bennett and Richard E. Byrd accomplished the first flight over the North Pole on May 9, 1926. Piloting a Fokker Tri-motor, Bennett took off from the Norwegian Arctic island of Spitsbergen, crossed the pole and returned 16 hours later. Although some have contended that Bennett and Byrd did not make it all the way to the North Pole, the flight — 1,545 miles amid extremely strong winds — was nonetheless a significant accomplishment. Along with Byrd, Bennett received the Medal of Honor for the flight, and he became the namesake of New York's first municipal airport, Floyd Bennett Field. (Section 3, Grave 1852-B)

Richard Byrd (1888-1957) — An Arctic explorer and naval aviator, Byrd was the first person to fly over both poles of the Earth. On May 9, 1926, in a Fokker Tri-motor piloted by Floyd Bennett, he traversed the North Pole in a 16-hour flight over 1,545 miles. Along with Bennett, he received the Medal of Honor in recognition of his accomplishment. He made expeditions to Antarctica during the late 1920s and 1930s, achieving the first flight to and from the South Pole on November 28, 1929. The following month, Congress promoted him to rear admiral (retired). Byrd continued exploring Antarctica throughout his life; he was 67 years old at the time of his last expedition, in 1955. (Section 2, Grave 4969)

Roger B. Chaffee (1935-1967) — A member of NASA's third group of astronauts, Lt. Cmdr. Roger Chaffee served as capsule communicator for Gemini 4 in 1965, and was selected to be a pilot on the first Apollo mission. On January 27, 1967, a few months before its scheduled launch, the Apollo 1 capsule caught fire during a launch rehearsal at Cape Canaveral, Florida, killing the three astronauts aboard: Chaffee, Lt. Col. Virgil Ivan "Gus" Grissom and Lt. Col. Ed White. Chaffee and Grissom are buried next to one another. (Section 3, Grave 2502-F)

Charles "Pete" Conrad Jr. (1930-1999) — The third human to walk on the moon, Cpt. Pete Conrad commanded the Apollo 12 mission from November 14 to 24, 1969. Selected for the second group of NASA astronauts in 1962, Conrad went to space four times: as copilot of Gemini 5 (1965), command pilot of Gemini 11 (1966), command pilot of Apollo 12 (1960) and commander of Skylab 2 (1973). After retiring from NASA and the Navy in 1973, he held executive positions at the McDonnell-Douglas Corporation, and in 1996 helped crew a Learjet that set a record for fastest around-the-world flight. (Section 11, Grave 113-3)

Robert Edwin Peary (1856-1920) — On April 6, 1909, Robert Peary led the first successful expedition to the North Pole, joined by his colleague Matthew Henson and four Inuit assistants. While in the U.S. Navy Civil Engineering Corps, Peary had made several previous Arctic expeditions, setting a "farthest north" record — for which he received the National Geographic Society's Hubbard Medal — on a Greenland expedition in 1906. In 1911, Congress promoted Peary to rear admiral. The monument over his grave (pictured, above) features a large, white granite globe, with a bronze star marking the North Pole. (Section 8, Grave S-15)

David M. Walker (1940-2001) — Selected as an astronaut in 1978 for the new space shuttle program, Capt. Walker logged more than 700 hours in space during four missions: STS 51-A, Space Shuttle Discovery, 1984; STS-30, Atlantis, 1989; STS-53, Discovery, 1992; and STS-69, Endeavor, 1995. The May 1989 Discovery mission, which Walker commanded, launched the Magellan Venus probe. (Section 66, Grave 5191)

Charles Wilkes (1798-1877) — Charles Wilkes was a U.S. Navy officer, Civil War veteran and explorer. Known for his skill with navigational instruments, he commanded the U.S. Exploring Expedition of 1838-1842 (also known as the Ex. Ex. or Wilkes Expedition), which mapped large portions of the northwest American coast, the Pacific and Antarctica. The expedition confirmed that Antarctica is a separate continent, and established U.S. naval power in the southern and eastern Pacific. Wilkes's Civil War service was controversial, resulting in an 1864 court martial; however, the charges were dropped and he was promoted to rear admiral (retired) in 1866. (Section 2, Grave 1164)

See also:

Navy Monuments and Memorials at ANC

Mast of the Maine (USS Maine Memorial) — The Mast of the Maine overlooks the remains of those who died when the ship exploded off the coast of Havana, Cuba on February 15, 1898. As Cubans were fighting for independence from Spanish colonial rule, President William McKinley ordered the Maine to Cuba to protect U.S. political and economic interests on the nearby island. On the night of February 15, an explosion in Havana Harbor tore through the ship's hull, killing more than 260 sailors on board. The United States blamed Spain for the disaster (later determined to have likely been an accident), which led to the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in April 1898. "Remember the Maine!" became pro-war Americans' signature rallying cry. Those who died in the Maine's explosion were initially buried in a Havana cemetery. On March 30, 1898, Congress authorized their remains to be disinterred and transferred to Arlington National Cemetery. On December 28, 1899, 165 sets of remains were reinterred in Section 24 with a full military honors service. The Maine, meanwhile, lay at the bottom of Havana Harbor for over a decade. Calls to raise the ship heightened in 1908, the 10th anniversary of its destruction. In March 1912, the Navy transported the ship's mast to Arlington, where it was placed onto a granite base meant to represent the turret of a battleship. The names of those who died aboard the Maine were inscribed onto the base. The memorial was unveiled and dedicated by President Woodrow Wilson in a large public ceremony held on May 30, 1915, pictured above. (Section 24)

USS Forrestal Monument — In front of Memorial Amphitheater, a group burial marker commemorates 18 sailors who died aboard the aircraft carrier USS Forrestal during the Vietnam War. On July 29, 1967, while patrolling the South China Sea, the Forrestal caught on fire. Caused by an electrical surge on the flight deck, the fire spread quickly and detonated a bomb. One hundred thirty-four personnel lost their lives in the accident, one of the worst in the Navy's post-World War II history. The commingled remains of 18 of these men lay beneath the monument. (Section 24)

USS Monitor Monument — The remains of two unidentified Civil War sailors, recovered from inside the turret of the first American ironclad warship, Monitor, were properly buried at the cemetery in 2013 with a ceremony that honored the other 14 Monitor crew members lost as well. The monument's inscription contains the names of all 16 Monitor crew members. (Section 46)

► Read our blog post to learn more about the Monitor and the remarkable story of the two unknown sailors, whose journey from the Monitor wreck site off North Carolina to Arlington spanned a century and a half.

USS Thresher National Commemorative Monument — Dedicated on September 26, 2019, this monument commemorates the service and sacrifice of the crew of the USS Thresher (SSN-593), the world’s most technologically advanced nuclear-powered submarine of its day. On April 10, 1963, Thresher sank during deep-diving tests off the coast of Massachusetts, killing all 129 personnel aboard: 16 officers, 96 enlisted sailors and 17 civilian technicians. It was the deadliest accident in submarine history, leading the Navy to establish the SUBSAFE Submarine Safety Program. The monument's inscription states, "In honor of the 129 men lost aboard USS Thresher (SSN-593) and their SUBSAFE legacy.” (Section 2)

Image credits, from top: